Curiosity and Age

Let’s go back to the beginning. We know kids are endlessly curious. Three-year-olds ask their parents about 100 questions a day.

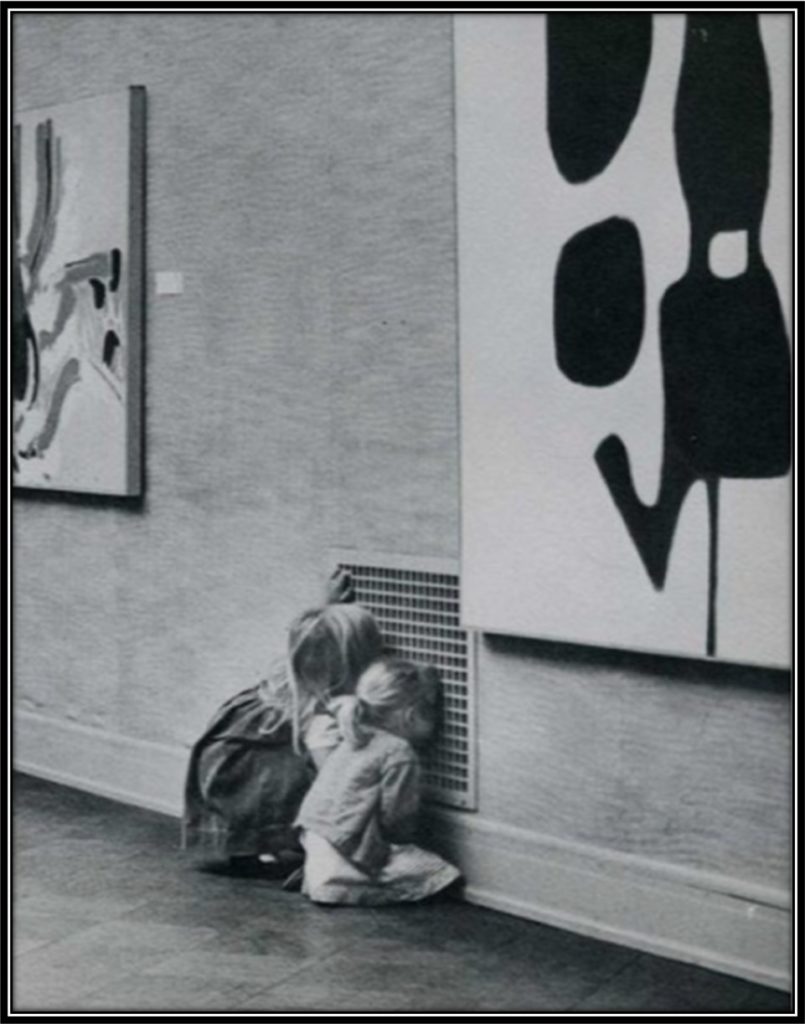

I love this photograph because it shows the wonder of the world through the eyes of a child. Here they are at this incredible museum with all the art that everyone is supposed to look at on the walls and what do the kids do? They want to see what’s behind the vent. When I look at this picture, I wonder what they saw back there. Do you?

When did you stop wanting to look behind the vent? What stopped you? Did someone literally say, ‘Don’t do that’?

We have seen that they begin with this wonderful level of curiosity and then around the age of 5, curiosity in children begins to dwindle.

In Sir Ken Robinson’s incredible TED talk about whether schools kill creativity, he acknowledged that we created an educational system that educates people out of their capacities. To meet 19th-century industrial job requirements, we created a hierarchy in education where math and science were the top priorities, and creative thinking was at the bottom. As education began to reward for more top-tiered skills like math and science, the system became about creating more academics, which led to the undergraduate degree becoming less useful, requiring more and more top-tiered skilled degrees. This system has been detrimental for curiosity and creativity, which are fundamental for innovation.

To understand the impact this has had, it helps to look at the effect on children. Professor George Land created an assessment as part of his work with NASA to test for creativity. In the process, he studied children to see how their levels changed throughout time. At the age of 5, 98% of children were creative geniuses, at age ten that number fell to 30%, at age 15 it dropped to 12%, and by age 31, only 2% were creative geniuses. It is critical to understand why this occurs.

If we look at two kinds of thinking that take place, it helps us see where we have created obstacles to curiosity and creativity.

Consider that we have divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking is about imagination and creating possibilities, whereas convergent thinking is about testing and criticizing. Land likens divergent thinking to the accelerator and convergent thinking to the brake. The problem is that our education system encourages both to occur at the same time. The result is that they come up with new ideas only to judge and criticize them into non-existence. A perpetual monologue in our mind shuts down potentially valuable ideas. That voice can stop further exploration.

As you look at what we know from the Sate of Curiosity Report done by Merck, curiosity levels are higher in larger organizations, Millennials have more of it than Gen Z or Boomers, the U.S. is more curious than China but less than Germany.

There has never been a more critical time to cultivate a culture fueled by curiosity to ensure the survival of organizations. With groundbreaking technologies such as CRISPR DNA sequencing, 3D printing, robotics, and AI, organizations must operate at warp speed. They must adapt quickly to thrive.

Leaders at Google have long-viewed learning agility and curiosity as a leading predictor of success. They place it above intelligence and education. However, we only see about 15% of employees who have a strongly developed sense of curiosity.

While it might seem intuitive to hire for experience, Harvard Business Review published research that showed experience is not trivial, but it can be perpetually overrated. It can be more important to focus on resiliency, adaptability, and those who embrace curiosity to learn when circumstances can fluctuate.

In one study of global pharmaceutical leaders, those who had high levels of curiosity received twice as many promotions as those with low levels. The desire to learn accounts for 18% of why a person is promoted.

If we can develop curiosity, we can improve information seeking, enhanced learning, unprompted questions – and that can help individuals perceive change as less stressful and therefore adapt more easily. For organizations, improving curiosity translates into improved innovation, engagement, and just about every other factor that ties into productivity.

Does our curiosity change as we age? Does it decrease? Do we lose our childlike curiosity as we grow?

Do Millennials tend to have more curiosity than Baby Boomers, or less? Is age a factor in determining our curiosity to learn new things or to pursue new ideas? Just curious!

According to Robert Stokoe, director of the Jumeirah English-Speaking Schools in Dubai, United Arab Emirates [1]

‘‘Three-year-olds, on average, ask their parents about 100 questions a day, every day! However, by the time they are ten to 11 years of age they’ve pretty much stopped asking. Of even greater concern is that by the age of 25, only two percent can think outside the box. Curiosity seldom survives childhood. Adult creativity is still powerful, but there is just not enough of it. It can be said that the creative adult is the curious child who survived.’’

Dr. John Bowlby, a famed psychoanalyst who conducted a wide range of studies on curiosity and age, concurred with Stokoe. However, his acknowledgment included a qualifier.

Best known for his child attachment theory, this psychoanalyst wrote that intuitive curiosity found in young children can be greatly influenced by their mother or caregiver to whom they become feverishly attached. “Secure infants,” Bowlby stated, “who view their caregiver as a secure base, feel safe to explore their environment, knowing they have that secure environment. Insecure infants, on the other hand, who do not feel the safety and security of their caregiver, are far less inclined to explore their environment.” [2]

Carol Dweck [3], author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, described the phenomenon in simple, binary terms. Children are greatly affected by their caregivers in terms of putting the child into either a growth or fixed mindset. Dweck described the language that tends to encourage a growth mindset, phrases such as “Let’s find out,” “I wonder,” and “What if . . .?”

Every mind is born with the instinct of curiosity. We all come into the world curious, an innate gift which newborns demonstrate as soon as they are born when they begin to look around. Robert Stokoe [1]

In light of Bowlby’s qualifier, if we take Stokoe’s article at face value, our curiosity is indeed strongest as a child but tends to lessen as we age. If you’ve ever played iPad games with an eight-year-old who is catching on more quickly than you are, you might tend to agree.

Then there is the dreaded 8-10 year slump.

Educators describe a phenomenon in which children between the age of 8-10 years show a declining interest in reading and studies in general. Some say they’re developing interests in video games, organised sports, and other after-school activities. Others say our education system tends to overwhelm them with tests and other assessments. By the age of 8-10 years, students feel burned out.

This phenomenon may be more of a commentary on our education system than on childhood development. As one educator said, “By the age of 8-10 years, kids go from learning to read to reading to learn.”

Research has shown that our brains go into the beginning stages of decline as early as our mid-twenties. But does that decline include curiosity as well? In 2014, the Public Library of Science published a study designed to answer that and related questions.

Researchers had 3,305 volunteers ranging in age from the mid-teens to the mid-forties play a video game called StarCraft 2, which required quick thinking and real-time strategy. The objective of the study was to gauge whether we begin to rely more on our experience and less on our curiosity as we age.

The researchers began the study with the premise that we employ our experience to compensate for our age-related decline, creating what they called “over-the-hill intuition.” Do our brains begin to slow down as we age, therefore causing us to compensate by relying more on our experience?

This game required the participants to make a myriad of dynamic adjustments as they executed a game plan. While each player performed a variety of tasks, they were also required to form a long-term strategy.

The results from this game were both predictable and surprising.

The researchers concluded,

“The speed with which the volunteers made decisions and shifted between tasks definitely declined with the older participants, with the first signs of cognitive decline beginning around the ripe old age of 24.”

I could not, at any age, be content to take my place by the fireside and simply look on. Life was meant to be lived. Curiosity must be kept alive. One must never, for whatever reason, turn his back on life. Eleanor Roosevelt [4]

That research concluded that there was cognitive decline as we aged but showed no decline in curiosity. Related studies have suggested that while our brains may experience decline as we age, our curiosity remains intact and may actually increase. That appears to be particularly true when confronted with topics that may not have interested us as children.

For example, when I was young, I had no curiosity or interest in anything related to history or social studies. However, visiting Pearl Harbor as an adult, I became more interested in learning about the Pearl Harbor bombing in 1941 and related events in ways I would not have earlier.

Safety

Becky Thomas, an author and executive coach who works extensively with generational issues in the workplace, has pointed out factors in the curiosity of different age groups.

Thomas’s work has echoed the same theme of John Bowlby’s studies with children, adding that the opposite dynamic can also occur as we grow older. The lack of safety can enhance one’s curiosity.

Thomas explained:

“The safety and security an individual feels about their surroundings is clearly a factor regarding curiosity more than a person’s age. But consider that Millennials grew up in a time with very low trust, due to the Financial Crisis, the events of 9/11, parents losing their jobs, etc. So, because they have low trust, they’re apt to question things at a higher rate than a Gen Xer or baby boomer would at their age. Earlier generations grew up in a very ‘safe’ era and typically trusted leadership, so there wasn’t the questioning and curiosity in the same way there is now.”

Thomas continued, “Curiosity is also heavily tied to the value the individual places on learning. Millennials, or young professionals, are possibly more curious because they are still seeking to learn about issues their older counterparts already know. But, overall, the safety of the environment and the value the individual places on learning tend to be stronger variables than age in determining one’s curiosity.” [5]

Quality of life

Going one step further, researchers Gary Swan and Dorit Carmelli conducted a study that showed, as we age, curiosity can add to the longevity and quality of our lives, up to thirty percent longer and a higher quality of life.

The study, funded by the National Institute of Aging, examined the curiosity levels among nearly 1,200 white men averaging age sixty-five. It also factored in physical health risks, including blood pressure, cholesterol level, and history of smoking, cancer, depression, or stroke. The subjects were followed for five years to see if curiosity had any differentiating effects on the length or quality of their lives.

The results showed a strong correlation between curiosity and strong physical and psychological health. They were not startling, but the strength of the correlation between the two was surprising.

After separating out the physical variables, the men who showed higher levels of curiosity were thirty percent more likely to live beyond those five years than the men with merely average curiosity. A related study of more than a thousand women found similar results.

Curiosity and coping

Why would higher levels of curiosity relate to better survival in older adults, the researchers were asked? They explained that higher levels of curiosity can provide an improved ability to respond to the challenges of aging, such as limited mobility or changes in living arrangements.

“Those with higher levels of curiosity showed better coping skills with new challenges or new experiences. They were also more adept at establishing new friendships and showing new ways to solve problems. The adaptive value of exploratory, problem-solving behavior is fundamental to living longer.”

The researchers concluded:

“When we are children, our curiosity leads to effective intellectual and emotional development. When this child-like trait continues, it enhances our ability to live longer with more active lives.”

Imagine children as bundles of curiosity with an innate desire to discover the world around them. Now imagine shutting off or discouraging that natural tendency.

The loss of curiosity is not a function of aging but a learned fear of knowledge.

Discussion

What happens to creativity and curiosity as we age? We will find out more in Week 2 of this course!

What other features and attributes change as we age? And how would you tackle maintaining your curiosity as you age?

In the comments below, explain to your fellow peers what you have taken away from this step.

References

1. Stokoe R. Curiosity, a Condition for Learning. Questia.com. 2012 [cited 27 August 2020]. Available from: https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1P3-3009007551/curiosity-a-condition-for-learning

2. Bowlby J. Attachment, communication, and the therapeutic process. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books; 1988.

3. Dweck C. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Penguin Random House; 2006.

4. A quote by Eleanor Roosevelt [Internet]. Goodreads.com. [cited 27 August 2020]. Available from: https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/395328-i-could-never-be-content-to-take-my-place-by

5. Hamilton PhD D. Cracking the curiosity code: The key to unlocking human potential. Gatekeeper press. Columbus, Ohio: Dr. Diane Hamilton; 2018.