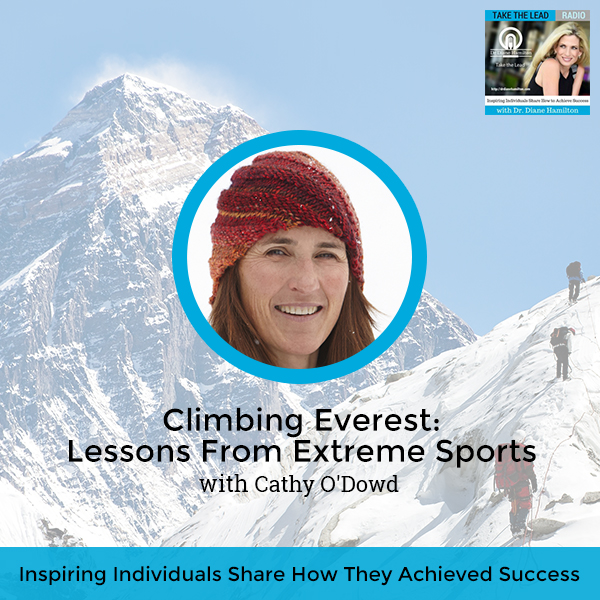

Contrary to what most assume, we can find moments of reflection even in the most hectic and thrilling times. Not only in the stillness of meditation can we ponder and understand ourselves more. Extreme moments also lend themselves to make us realize what we are capable of. In this episode, Dr. Diane Hamilton speaks with Cathy O’Dowd, a motivational speaker and the first woman to climb Everest from both sides. Cathy shares with us how that adventure went and gives insight into the world of extreme sports—breaking myths and assumptions and shedding light into the values we can learn and apply in our lives. Here, she relates it to corporate settings where risk management and problem-solving in high-stress situations is concerned. Breaking into a male-dominated field, Cathy then talks about female empowerment in mountaineering and rethinking what strength looks like. Find inspiration and beauty in pushing through difficult situations from this great conversation with Cathy.

I’m glad you joined us because we have Cathy O’Dowd. Cathy is the first woman to climb Everest from both sides. She’s a motivational speaker. She works with team dynamics, leadership, and innovation. Her story is a fascinating one. You’re not going to want to miss this one.

—

Watch the episode here

Listen to the podcast here

Climbing Everest: Lessons From Extreme Sports With Cathy O’Dowd

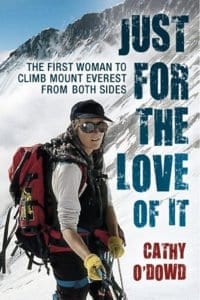

I am here with Cathy O’Dowd who is a South African Mountaineer. She is the author of Just for the Love of It: The First Woman to Climb Mount Everest from Both Sides. She shares insights with her corporate audiences through story-driven expedition case studies. She is a well-thought-of speaker and she’s got an interesting story. I’m excited to have you here. Thank you for being here, Cathy.

It’s my pleasure.

You’ve got quite an interesting background of what you’ve done in terms of expeditions and things. What led you to be this person that can do this amazing thing? What’s your background? Can you give a little backstory?

None of it was obvious. If you have taken the girls at my school, I went to a school that was only girls. Ask who is most likely to become famous for sporting achievements? My name would have been at the bottom. I was that girl who was always picked last when you were doing that horrible team pick thing and the two team captains would end up looking at each other and saying like, “Her? Do we have to?” I rest forward, all those ladylike sports they did at school, hockey and netball. I went to the school that was to turn off the lady. I grew up in Johannesburg, which is a big city on a huge grass plain. Parents who didn’t do any of those. We went for day walks on the summit on holidays. South Africa is not a mountaineering country. We have little heritage of mountaineering. None of this was obvious. I think what I did have was a quiet determination to go my own way.

Some of it being introverted and some of it being not terribly socially well-adjusted. I’m not terribly good for making friends, but then I quietly and potentially on my own do my thing. That included when I got to university in South Africa discovering rock climbing. For the first time finding a physical activity is rarely engaging. Nobody had to lose. It wasn’t win or lose. It wasn’t competitive. It wasn’t a rah-rah team sport. It was this quiet, deeply personal, physical and mental challenge. It’s about problem-solving. People assume that extreme sport and mountaineering and so on, is going to all be about achievement and conquering things, which is terrible and misunderstanding of the point. It’s all adventure and problem-solving.

It’s being curious. You look at something and go, “I wonder if I could deal with that. What would it take to deal with that? What skills would I need? What experience? How would I get that?” When you think you’ve got something to move into that space, I go, “How am I going to manage this environment, solve these problems, deal with the unexpected using the tools and the skill I brought with me?” That for me is what climbing is about. All of it. Whether it’s a local mountain or Everest, it’s a process of curiosity and problem-solving.

I have entered in some rock climbing competitions, and you may or may not know, I wrote a book on curiosity and I have to agree with you completely that this is such a thing for me. When I go rock climbing, I mostly do the rock climbing gym. You have to manipulate yourself in such a way. It’s all a puzzle to me of how to do it. I love that as one of the types of exercise I get in because it is mental. It is that, how can I get to that next position? You have to calculate these things in your head.

I’ve had Erik Weihenmayer on the show. I’m sure you’re familiar with him, a first blind man to climb all the top peaks. I saw him at my rock climbing gym and I watched him. It was fun to see how he manipulated his body to do it because he wasn’t even using his eyes to do it. It is a mentally challenging thing. I love that you described it that way because that’s how I see it. Other people go, “Why would you want to do that?” Sometimes I tell them I like rock climbing because it’s not an exercise for me, I see it as a mental challenge for sure. What do you think? What were you going to add?

That’s one of the things that are misunderstood about the so-called extreme sports. People say to me, “What do you do to relax?” I go climbing and I go skiing. It’s a need for a certain type of people. The reason what looks like it’s an arduous physical activity with considerable risk management involved. Why is that relaxing? It’s relaxing because it requires complete engagement in what’s happening. The thing about lying on the beach or lying on the sofa, it’s your mind and still be going at a million miles a minute, worrying round and round about whatever it is. Whereas these activities require complete physical and mental immersion in what you’re doing. It’s an exercise in being rarely present in the now and being engaged on every level. That for me is why it’s relaxing.

[bctt tweet=”Extreme sports is an exercise in being rarely present in the now and being engaged on every level. ” username=””]I have to say, it’s exhausting though. Your forearms hurt.

That’s good too. That feeling when you’re in bed, “I’m about to sleep because I’m physically tired and I’m mentally tired,” as against, “I’m lying in bed knowing I ought to sleep because I need to rest but my mind is going a million miles a minute and I can’t disengage from that.”

I know exactly what you’re talking about. It is the kind of thing that puts you out when you’re done, you’re just done. When you’re climbing a mountain, it’s a little different than being at the rock gym. Because when you’re done, what happens when you hit a wall? I’ve seen all the movies. I know that you got stuck in some of those that they talk about. You were trapped in that storm. The movie, Into Thin Air, you got stuck in that. You’ve had a lot of scary things happen and traumatic things from your experiences. Do you want to talk about some of that?

I’d like to start with a couple of caveats. It’s only the most extreme events that make best-selling books and get turned into movies and give us the content to write books, speeches and that thing. People are looking for drama and disaster essentially. What that doesn’t affect is the fact that 99% of expedition authority is boring everybody except the people who went on them because they were meticulously planned, followed by being well-executed and everybody came home with nice photos and said that was fun.

There may be an engaging experience, but the result is that people somehow, as soon as you set foot of the mountain storms, avalanches and death-defying disaster is around the corner. It’s not most of the time all totally under control and placid. That being said, you’re always carrying the possibility that things might go wrong. It becomes about your mental approach. It’s not about being a Pollyanna and pretending it won’t happen and it will be fine. It’s about looking at what might go wrong. Being realistic about the actual percentage chance that it will happen. Being realistic about what your strategy is. Where your strategy is everything from your experience to your skillset, the physical tool to the team you’re with, the time of the year to your evacuation plan, all of that.

It’s not Russian roulette, it’s not fighting with death or anything like it. It’s risk management. I find that process quite engaging. Trying to look at risk and say like, “Let’s get realistic rather than dramatic.” How likely is this to happen? Why would it happen? What can we do to stop it happening? If it does happen, what will we do to get ourselves out of this situation? When you end up in one of those moments, like being caught in the storm on Everest, the famous spring of 1996. It’s a storm in which on our side of the mountain, five people were killed, two of them are famous mountaineers. My team and I were trapped at the highest camp at 8,000 meters on Everest during the storm. The thing that doesn’t come across in books and movies is being trapped in a storm is boring. You can’t sleep because something might go wrong. You’re sitting there in the middle of the night, fully dressed because of the fear that your tent will tear. You can’t have the tent tear open because the fabric gets sliced by a piece of ice in the wind and you’d be sitting there in your thermal underwear and your socks. You’re sitting there fully dressed, cuddling your sleeping bag, drinking cups of coffee, and you’re worried, but also nothing kept coming.

How long did you get stuck like that? How cold is it?

It was for 36 hours.

No sleep at all?

Just for the love of it: The first woman to climb Mount Everest from both sides

You can’t even be awake for 36 hours. Between you, you’re drifting or sitting around, chatting and eventually you end up having mundane conversations about normal things despite the fact that you’re stuck in what might be a high-risk situation but isn’t as long as your tent holds.

What if your tent doesn’t hold? What happens?

If your tent doesn’t hold, you’re going to have to deal with it. You have to start trying to get yourself down the mountain or you have to try and create some shelter until the weather improves enough to get yourself down the mountain. There’s an interesting balance between understanding what the risks are and have already thought of at least an entry strategy to deal with them. You don’t want to be trying to come up with clever rescue plans when you’re highly stressed. That’s why we do scenario planning beforehand. If this happens, what would we do? If we do that, it might lead to A, B or C. What would the strategy be for A, B or for C? You can’t foresee everything, but you can at least implant in your mind a couple of potential exit strategies. Spend a little bit of time visualizing what it would take to start to execute that strategy, which means that when things go wrong and you’re highly stressed and possibly you have to make choices quickly, your mind already has a couple of options to go to.

One of the things that definitely does happen in these high-stress situations isn’t that you stop thinking clearly completely. Some person who’s going to panic and get hysterical shouldn’t have taken up mountain climbing. Know yourself well enough not to do it yourself. Few people on the mountain are fairly pragmatic in the face of risk. What does happen though, when you’re highly stressed and tired, is you lose some of your metaphorical peripheral vision. Your ability to think of the clever, unusual, unexpected solution. Your ability to problem-solve gets reduced to your core competency, the most obvious stuff. I think that’s one of the risks. Not that you can’t make choices. You can, but you don’t have the energy to make creative choices to see the unexpected way out. One of the problems with hindsight when everybody sits down and says, “Why didn’t you do X, Y and Z?” The answer was, “Because we were tired and stressed that the only thing we could think of is A, B and C. You want me to be 26 letters down the alphabet with alternative options.”

You had to make some tough decisions because you got a few hundred meters from the summit and one try. What happened in that attempt?

This was my second expedition to Everest. I had already got to the top one. We were trying on the other side. A couple of hours planning time from the summit, but on our summit day and high on the mountain at 8,700 meters, we came across an American woman on the mountainside by herself. Like everything, there was a fairly complicated story about why she ended up here on her own, but she’d already been up there for a long time. We thought she was dead until she managed to move a little bit. This isn’t encountering somebody who’s sitting there saying, “Can you help me? I sprained my ankle.” This is someone who’s hours from death to completely incapable of helping themselves. She couldn’t even sit upright. She had no muscle tension at all. When we try to bring around into a sitting position, she just flopped like a ragdoll. She has no ability to help her at all. One of the questions is, what do you do? There’s a certain perception in the general public that mountaineers at 8,000 meters don’t care about anybody else.

You saw and go, “I’ve got to go. She’s dying, tough luck. Step over her and go to the summit.” It’s completely untrue. What people from the city are forgetting, they think it will do something. What would they do in the city? They’d get out their mobile phone and they’d call somebody else. They’d call the police, they’d call the ambulance. They’d call 911 and then, “I’ve done something and the professionals will fix it.” That person could still die in the ambulance on the way to the hospital or die in the hospital. The thing on the mountain, there’s no one else to call. If a rescue is going to happen, it’s us. We’re not carrying extra medical gear. We’re not carrying spare oxygen bottles. We don’t even have a spare oxygen mask to give her. We don’t have a stretcher. I’ve never tried deadlifting another adult human being, let alone 8,700 meters in temperature of minus 30, and then try and climb down the steep and technically walk in ice slope not for twenty minutes but for days. What I’m trying to say with all of that is sometimes you can’t save somebody’s life. Sometimes you know that and they aren’t dead yet and you still can’t save them. It doesn’t matter how much you stand there saying, “When there’s life, there’s hope.” You need a plan and there isn’t one. That’s what happened with Francys Arsentiev, an American woman because there wasn’t any plan that we could execute that was going to save her life.

Was she able to speak? Did I see that she read, “Don’t leave me?”

Yes and no. These things turn out to be complicated. She was speaking, but she wasn’t speaking in the sense that you and I are speaking. She couldn’t hold a conversation. She could say three things over and over like you’re a stuck record. She couldn’t respond to anything we said to her, for example. It was as if in the vestiges of her mind, these were the last three words, but none of that helped it. It didn’t make it any easier to do anything for her. It made it harder to realize that we couldn’t do anything for her. There’s a big space between being alive and being dead, but most of us don’t get to encounter personally because of death medicalized. It happened in the hands of professionals in hospitals, mostly. On an individual level, most of us don’t see this anymore.

[bctt tweet=”It’s only the most extreme events that make bestselling books because people look for drama. ” username=””]You had to see this and you had to eventually leave her to save your own life. What trauma does that do to you later? Does that keep coming and flashing back to you? How do you get past that?

This is one of these difficult questions. I’m going to give you a completely honest answer, but I also know that for some of your audience, it’s going to make me sound color. I haven’t carried trauma from that afterward. It was certainly traumatic at the time, but on the other hand, you’ve got to be thoroughly pragmatic. Eight thousand seven hundred meters of the mountain is no place to collapse because you’re traumatized. All you’ve done is endanger yourself and endanger the rest of your team. You have to hold it together. It takes a certain pragmatic personality to potentially put yourself into these situations. At the time, we did what we had to do to help us as long as we could until our own lives are beginning to be in danger, and then to retreat, which is what I did. We didn’t go on to the summit. We went down afterward. I couldn’t get it back together. Intellectually I could say it makes no difference to her whether we go onto the summit or we go down. Emotionally I couldn’t walk past her and refined my focus to climb back. In the end, I climbed for joy and that sucked the joy out of all things.

I can’t imagine it wouldn’t. It’d make it difficult. It brings to mind the movie Vertical Limit where if you ran into a body there later, does she get covered in snow and no one else has to go past this? What happens with her body? Do you have to see other people as you’ve been hiking?

Yes, I have but not often. The numbers on Everest had gone up exponentially. This is a story that comes many years ago. Everest in 2020 is a little different because it is not so crowded. Even back then they were a handful of bodies. What normally happens to bring a body all the way back down to return it to a family, you can do that low down on the mountain, but high up on the mountain, it’s too risky. You don’t want to kill people while attempting to retrieve a body. High up on the mountain, if possible, the body gets tipped on the side of the mountain. Something that gets them off for climbing route. That’s not always possible. They do freeze in. If you think about it, the place is like a giant, deep freeze. It’s like keeping a body in the morgue. They don’t rot. It’s too cold. They defecate a little bit. What it looks like if you go past them? It looks like they’re sleeping. They’re not lying and rotting. The way I’ve thought about it, and it’s a coping mechanism, but it’s the one that works for me. It’s an empty suitcase. What was there that made it a living person has gone however that works. Wherever it goes, and what is lying on the mountainside is the suitcase.

When you get down the mountain, you’re able to inform people. If somebody wondered what happened, people at least know what happened to this person.

All this answer is a little more complicated than that. You’ve got to be sure who it was. We found her. We had met her once before, but she had been up there for so long and the frostbite that she had suffered made her look a lot younger because her face had frozen, waxy white and smooth. It’s almost like the old-fashioned China doll. It made her even look many years younger than she was. Everybody is incredibly bonded up in clothing. Maybe she was an American woman when we met a couple of weeks ago and had a cup of tea with, but maybe not. How do you know?

Do you take pictures? You guys have your cameras and things.

I did take a picture. I have never let them be published. I did have media afterward who wanted copies of pictures with the body and I said no, but you do in case it’s useful for identifying the body or for the family. Eventually, people at base camp started asking. Based on that, we confirmed who she was, but we then knew that she had a child in America living with the ex-husband. He hadn’t been abandoned by his mother. Nobody wants the son to find out in the media. The Russian team, because she was climbing with them then had to inform their embassy in China because it was in China to do this. That takes days. Nobody can say anything until we know that the embassy has officially informed the family back in the United States, which means several days of people knowing that we’ve turned back. Not knowing exactly why, which was a bit strange. We’re all carrying pocket satellite telephones. It’s a little easier, but this was many years ago. It was a lot less technology.

You probably have experienced a lot of injuries from it. Have you had to deal with frostbite and other issues on your own?

Climbing Everest: People assume that extreme sport and mountaineering are all be about achievement and conquering things when it’s all adventure and problem-solving.

I have never been injured. I’ve never had frostbite. I know people who’ve had all sorts of things, but none of this is inevitable. A little bit of it is bad luck. A lot of it is people have made a mistake and it’s hard not to make mistakes. No human being goes through life without having made a whole bunch of mistakes. Even when I say people made mistakes, that doesn’t mean you’re pointing the finger of blame saying, “That was excellent.” No, that was a mistake and you were unlucky that it had a serious consequence as against the kind of mistake where you get away, which is what mostly happens.

When you’re doing this, is it walking? Is it climbing? Are they 5.7 or are they 5.10? What are you doing? I’m trying to envision this for people who aren’t rock climbers if 5.7 is not a hard climb as a 5.10. Are you having to use your hands and do all that?

It’s potentially all of it. I’ve done it. I’ve climbed for many years, so I do sport climbing, trad climbing, and hardcore rock climbing. I never quite managed 5.12A, but 5.11B. I get a top end of my sport climbing. I’ve done multi-pitch rock climbing in Yosemite. This mountaineering. When we talk about a mountain, it’s got a different grading system because it’s not just how steep it is. It’s a whole lot of other things that have to do with. Is this an avalanche slope? Is this a glazier full of hidden crevasses? There’s a skillset that has to do with risk recognition and risk management, which doesn’t exist in quite the same way in rock climbing. Here’s the stuff that was grade 5.7 or 5.9. Once you start with technical mountaineering, crampons and two ice axes, there’s a different grading system, which is about how steep your snow ice slope is. A mountain like Everest, the standard routes aren’t all that technical, which is a good thing because it’s cold and you’re wearing so much clothing and you have little oxygen. You aren’t performing it anything like your ability at sea level. There’s a reason why people aren’t doing 5.12 rock climbing at 8,000 meters. At least at the moment, it’s not possible.

In my vision, is it the worst, like a 5.7? How steep is it or is it not even that bad?

Rock climbing is less than vertical. There’s not much fun. It’s too easy. A lot of mountaineering is not yet vertical. You’re dealing with slopes anywhere between 40 and 70 degrees on the mountain like Everest. Even take the north side of Everest, which has a rock on it. It’s not vertical, but it’s broken. It’s like climbing up an incredibly steep squeeze slope with small vertical sections and small ledgers.

Are you using ropes?

Yes, but not always. You always want to do solo if you can because it’s much faster. Using a safety rope always slows you down. It’s got to be worth it.

When you talk about solo, how much does it freak you out to watch Free Solo and talk about Yosemite? Would you do something like that? Did you see that movie?

Yes, it’s going to be one of the great classics. The thing about Alex Honnold and movies like Free Solo, for most climbers, it’s astonishing to watch, but it’s not aspirational. It’s not what most of us want to do. People have climbed the route that Alex Honnold’s was on without falling off, but they had a safety rope in case they fell off. What’s rarely impressive about Alex Honnold is the mental control. His ability not to be sidetracked by the fear of what might happen if you make a mistake. I’m deeply impressed by what Alex Honnold did. I don’t look at that and think, “I want to do that,” or “I feel down because I’m not able to do that.” He’s way off of the far end of the spectrum.

[bctt tweet=”No human being go through life without having made a whole bunch of mistakes. ” username=””]It’s hard to watch that. My only reason I’m watching is that I know he must not have died when they made this. Otherwise, I’m sitting there going, “How could you do this?” These movies of all these people who’ve done these things. I liked the movie Adrift. It’s about a sailing thing. I know you’re going to be sailing to Antarctica and you’re doing all these other things too. You don’t just climb, you do a sea kayaking. What’s your next big adventure?

I feel like I still climb a lot. I think of myself as a climber, but I’m also prepared to say I’ve probably done the hardest climbing I’ll ever do in my life, unless I manage that 5.12A sports climbing. Sports climbing isn’t exactly how I risked height. I’m interested in taking my skillsets and expanding them. I still like it cold and wild. I’m still curious. I’m interested in trying to take on things a little different from what I’d done before. I’ve got two in that category, in the middle of summer going with a small team, six of us. We’re going to be doing an exploratory sea kayaking expedition along with the remote piece of the Greenland Coast.

That’s you’re fully self-sufficient in the sea kayaks, food and clothing. It’s cold waters kayaking between icebergs. We don’t know where we’re going to be camping, whether it’s fine places that we can reach the kayaks. I’ve always wanted to kayak in Arctic water. I’ve always wanted to visit Greenland. It takes my expedition knowledge from mountaineering and puts it into a different environment. That’s why I wanted to do that one. This one we’re still planning, so I can’t 100% say it’s a money thing, not surprisingly. What we’re trying to do is charter a yacht and sail from the tip of South America down to the Antarctic Peninsula. Hence, I’ve never sailed rarely. I don’t know how I’m going to feel about crossing the Southern Ocean in a yacht, but it’s only four days. I’ve got to be able to deal with it.

Don’t watch the movie Adrift before you go then.

Go and read up on the shackles and rowboat trying to get to South Georgia. The idea is to get to the Antarctic Peninsula, use the boat as bait and there are a couple of mountains, but there are no records that they’ve ever been planned. Those are our targets and we’ll be doing them on ski to climb up.

I’m from Arizona. You’re making me cold thinking about all this. All this stuff you do, I didn’t mention that you’re a motivational speaker and you speak in over 40 countries. You’re teaching executives what they can learn from you as a mountaineer. What’s the main message that you’re telling people from all of those?

The quick caveat is, let’s be honest, motivational speakers are entertainers. When these executives want hard content, they must be more likely to get themselves a dedicated business guru in their area of expertise. People like me are partly brought in to entertain and break up the monotony of the big business event. They’re also interested in examples of facing and overcoming a challenge with big obstacles. They are looking for ideas about the leadership of teams, difficult environments, about overcoming stress, about maintaining motivation, about problem-solving in difficult challenges. It’s not because they don’t know what they’re doing. The point is that they do know what they do, and they know what’s available to them within their particular area of expertise as business executives. They are looking for that little bit of extra information from somebody else’s area of expertise. Although I think it can sound a bit lame because somebody is listening to somebody talk about mountain climbing. What they’re looking for is that one more extra unusual idea that they couldn’t find elsewhere. One idea from that hour of time that could well be worth it for them. If not, it was a good story.

In addition to this speaking, you do a lot of charity work. You focus on female empowerment. What work are you doing in that area? I’m curious about that.

Mountaineering has always been this male-dominated area and it still is. Lots more women are doing it, particularly coming into rock climbing and gym climbing. The fact remains, women as a massive generalization are possibly slightly more sensible or slightly less risk infused. We are more likely to look at something and go, “I don’t see why you want to do that.” Possibly the high-risk things, men are always going to be a little more likely to put their hand up for them. The fact remains women are good once they get going. We talk ourselves out of it because we look at it and go, “That’s a man strength,” and we assume it’s all about muscle flexing biceps and stuff. We misunderstand what kind of strength is needed and what strengths that we as women can have.

Climbing Everest: When you’re highly stressed and very tired, you lose some of your metaphorical peripheral vision—your ability to think of the clever, unusual, and unexpected solution.

One of the things I’m interested in more charity work is reaching out to other women and talking about what strength looks like and what we truly are capable of. Not that you have to go out and climb mountains. It’s perfectly fine to say no. The thing is if you think you might want to, you can. Don’t talk yourself out of it. The two charities that I’m particularly involved with, the one is Astraia. We try and help with women’s education largely in third world countries. As an offshoot of that, a friend of mine runs a health charity in the Rwenzori Mountains in Central Africa, which is the first mountain I ever went on expeditions. That was where my journey started. With the money Astraia raises is running a health outreach program for these remote mountain villages where there isn’t even a road. The only way to the village is on foot. It’s incredibly important that mothers have the knowledge about how to look after their children in a healthy way in the village. Secondly, when to start walking the child down the mountainside to get to the hospital because often it’s left too late. We’re trying to bring knowledge to the woman in the villages so that they can make safer choices for themselves and for their children.

Everything you’ve done is inspirational for a lot of people. I think a lot of people want to know more about your book. Your book is Just for the Love of It: The First Woman to Climb Mount Everest from Both Sides. Is this a book that details what happened? Is it a life lesson? What is it meant to help?

It’s a memoir. It’s the story of my life on four expeditions to Everest. Two of them were successful, two of them were not successful, and the story that led up to that. It’s not designed as a bullet point life lesson. It’s a course for the love of it for a reason because I got sick of men writing books called things like Killer Mountain and The Death Zone. Your name goes on about look how brave, strong, and heroic I am. Most people, if they’re honest, we climbed because we enjoy it, even the difficulties. Even if having to overcome them and go, “I managed that. I’m still here. I’m still going. This is cool.” I wanted to talk about that. I tried to write a book that’s emotionally honest. Both about why I do it and the joy of it.

Also, the downside of that is it’s about being scared, tired and demotivated. The only woman in the tent full of men, wondering whether I’m good enough to be here or whether I’m a token woman who got added at the last minute for the sponsors. It’s all of those fears we carry with us. I’ve tried to write a book that’s emotionally open about what it’s like to be in these environments, trying to cope with these challenges, reach for success and also live and deal with the failures and the traumas.

I think that it sounds like an amazing book and your story is something I was looking forward to sharing. That was something that my small experience in rock climbing could appreciate from my perspective. Everybody could learn much from what you’ve done because you stretch yourself and I love how you tie it into curiosity. A lot of people would probably want to know how they can find out more about you, follow you, or find your books and all that. Is there some link or something you’d like to share?

The book is on Amazon, Just for the Love of It. My website is simply my name, CathyODowd.com. The best place to follow the adventures is Instagram, it’s @CathyODowd.

Cathy, this was interesting and fun. Thank you for being on the show.

My pleasure and I’m glad you’re a climber. It’s lovely to share that with you.

—

It was great to have Cathy on the show. I enjoy some of the true stories that people share on this show. I know we get a lot of strictly business-related stories. Eric O’Neill talks about his work catching the greatest spy in US history as an FBI agent. That was such a great show. I’ve had Molly from Molly’s Game, another movie because Eric’s movie was Breach that they made into his story. Molly’s story is a fascinating one. We have a lot of people share amazing things that they’ve done in their lives and how they take what they’ve learned. They use it to help motivate business people to see things from an outside perspective. That’s important because sometimes we have the same old talks, the same old things that we research. You get into this tunnel vision of what you read and what you learn. I try to get out of that rut because that helps build our level of curiosity and the need for exploration. That’s what I talk to companies about is how can we get organizations to recognize the need to get people not only discussing things across silos but to focus on some areas that they maybe never had thought about before.

[bctt tweet=”Women are very good once they get going. ” username=””]Some people might be disengaged because maybe they’re aligned improperly to a job that isn’t what they’re best at doing. How can you find out what they’d be best at doing unless you ask questions and explore opportunities and alternatives? It takes leadership to recognize the importance of curiosity from above. If we don’t get it from the top, the culture is often not going to have a lot of changes that we’d hoped to see. A lot of leaders are surrounded by people who maybe are yes men, yes women sometimes and trying to be respectful, but sometimes they don’t point out some of the changes that might need to be made.

It can help to get outside consulting and perspectives at times to see what we can do differently? How can we get people to be more engaged, motivated and innovative? A lot of that comes back to how do we develop curiosity. For me, that’s what I was looking to do when I started to write the book Cracking the Curiosity Code. I wanted to figure out how to fix that if people were not as curious as they could be. What was interesting to me was that there were no assessments available to determine the things that keep people from being curious. All the assessments out there told you how curious you were on a high to the low level, which is great, but if you’re not curious then what do you do? My goal was to figure out how we can figure out what keeps people from being curious so that we can help them move forward?

That’s what I did with the Curiosity Code Index. I’m honored that my research got the attention of Thinkers50 Radar of the 30 people for innovation and great ideas. That’s a huge honor because to me, I see them as the Academy Awards for business leadership and management ideas. That’s something I take seriously. I want to help organizations to improve their level of curiosity because I think we’re going to see a lot more research tying in how curiosity can help improve engagement, innovation and all the things that lead to productivity. We know that companies lose $500 billion a year for engagement according to Gallup. If people are aligned properly, we have a better chance of people being engaged.

If you’re asking questions and being interested in them, that’s only building your curiosity, but it’s also allowing them to feel that you care about them. That helps build empathy, which is a huge part of emotional intelligence, which is something that I’ve researched for my dissertation and beyond. Anything that could help build empathy and interpersonal skills is going to tie back in to reducing conflict and improving communication. We know to lose from tens of billions a year on up depending on which website you look at. That’s a huge area that we’re hoping to tap into for leaders to recognize the importance of curiosity. I’ve had many great experts on the show. Francesca Gino has been on and her HBR article is a must-read. If you haven’t read that about the case study for curiosity, that’s one of the better ones that’s been printed.

I think that there are a lot of motivation experts, there’s a lot of drive creativity experts. When you look at what leads to all those things, it’s curiosity. If we could recognize the impact that fear, assumptions or the voice in your head, technology, and environment can have on curiosity, that’s a huge first step. I have people take the Curiosity Code Index and you can see that at CuriosityCode.com or at DrDianeHamilton.com if you go to the Curiosity section. It’s an inexpensive quick assessment that takes ten minutes. You get a large PDF file like you would if you took DISC or emotional intelligence tests and that type of thing. You get your results instantaneously so that you can work on creating an action plan to move forward. Companies either give it to their entire company or people can take it individually online.

It’s an easily accessible thing. It goes hand in hand with the book Cracking the Curiosity Code, which I was fortunate to have the foreword written by Under Secretary Keith Krach, who used to be the Chairman of DocuSign. I can’t think of a more curious person and a more impressive person to write the foreword. It’s been receiving great testimonials by people who have backed it up. Steve Forbes was nice enough to write a great blurb. The same thing with Ken Fisher, Verne Harnish and the list goes on and on. The reason that this is catching everybody’s attention. I’m going to use this as an example of what curiosity is by explaining how it could be looked at like baking a cake.

Let’s say you want to bake a cake and you’re mixing these ingredients. You’ve got flour, oil, eggs and whatever you’re mixing. You put it into a pan and you put it in the oven. What happens? If you don’t turn on the oven, you get goo. Nothing happens. Your end product is not a cake. That’s what you want. In the working world, instead of a cake, our end product is productivity and we’re mixing together ingredients of creativity, innovation, engagement, and all these things. We’re putting it in the pan, but nobody’s turning on the oven. The spark is curiosity. That’s why I think this is resonating so much with people because everybody knew that ingredients were important, but nobody checked to see if the oven was plugged in and turned on.

Apparently, it’s not in a lot of places, so we want that. That’s why I do much speaking and work with all these companies. I’ve been fortunate to speak for Verizon or go out and include my videos for Wiley, these great groups. I’m doing research with different pharmaceutical companies. We’re looking at how we can incorporate this and making this organization more curiosity-driven. That’s the key to what we’re trying to do with AI taking over with jobs and moving people around into new areas. Where are we going to put them? Wouldn’t it be great to put them somewhere where they’ll thrive, engage, and be more productive because of all that? That’s what is important. A lot of companies are contacting me to have me either speak, train or do all these things to help them consult in the area of curiosity.

I’m happy to talk to you about that. You can find out more about that on my website at DrDianeHamilton.com. You can go right to the Curiosity Code Index, the certification program training or the book and all that. It’s all at CuriosityCode.com, which is also accessible on the website. I hope you take some time to explore that because I think it’s important. As we’re talking about all these issues, curiosity is such a huge topic and I wanted to cover that. I enjoyed this episode. Cathy was amazing. I’m always inspired by people who can do some of the things like what she’s able to do. It’s always nice to have a fellow rock climber even though I hardly am in her class of rock climbing capability on the show. I hope you enjoyed this episode. I hope you join us for the next episode of Take the Lead Radio.

Important Links:

- Cathy O’Dowd

- Just for the Love of It: The First Woman to Climb Mount Everest from Both Sides

- Erik Weihenmayer – past episode

- Astraia

- Killer Mountain

- The Death Zone

- Just for the Love of It on Amazon

- CathyODowd.com

- @CathyODowd – Instagram

- Eric O’Neill – past episode

- Molly Bloom – past episode

- Cracking the Curiosity Code

- Francesca Gino – past episode

- CuriosityCode.com

About Cathy O’Dowd

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

0 Comments