Respect trumps harmony. Whether you’re stuck in Antarctica for a year with people you don’t know or simply surrounded by your peers in the workplace from 9:00 to 5:00, you are bound to get into disagreements with others, and that’s okay. For highly-acclaimed international speaker and bestselling author, Rachael Robertson, the constant need to be liked by your colleagues is not just overrated; it is actually counterproductive. Selected to lead a year-long Antarctic expedition, Rachael created for her team a culture founded on mutual respect for each other and each other’s ideas. Drawing from that experience, she now teaches these leadership principles to the world through her speaking engagements. Learn more from her incredible experience and the things she learned from it about leadership, teamwork and inspiration in this conversation with Dr. Diane Hamilton.

I’m glad you joined us because we have Rachael Robertson here. Rachael led a team of eighteen people for a year in Antarctica and you can’t get out for a year, think about that. She learned so much and she’s got bestselling books based on it. I’m excited to have her here.

—

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here

Respect Trumps Harmony: Lessons From An Extreme Leadership Experience With Rachael Robertson

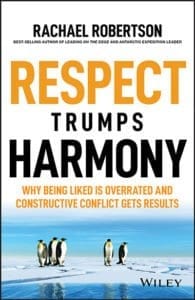

I am here with Rachael Robertson who returned to Australia after twelve months in the Antarctic where she successfully led the 58th Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition to Davis Station. She was the second female to ever lead a team at the station, and one of the youngest ever leaders. She is also the author of Leading On The Edge and she has her latest book which is Respect Trumps Harmony: Why Being Liked Is Overrated And Constructive Conflict Gets Results. It’s nice to have you here, Rachael.

Thank you for having me. I’m excited to be here.

This is going to be fun. I know you’re in Australia. Hopefully, we’ll have a good connection. It’s nice of you to do the show. I was interested in your journey. I know you managed a team of eighteen people through that long dark Antarctic winter and through all this that you’ve done. Before we get into that, I want to get a backstory. What leads somebody to want to do that? If you could give me your backstory, that would be great.

I would love to say it was a strategic decision, a career decision. I saw the job advertised in the newspaper. What intrigued me was that the Australian Antarctic Program, which is similar to the US Antarctic Program, they recruit people for quality. They recruit people with resilience, empathy and integrity. I saw this job advertised and I thought what a great way to recruit people for qualities rather than technical because you can teach technical. You can’t necessarily teach resilience and integrity. I only applied for the job. This is my fiendish plan.

I applied for the job thinking I’m going to get to the interview stage so I can hear what questions they’re using and I can copy their questions and bring them back to my team. What I didn’t realize at that time, they don’t have a job interview for this role. They have a bootcamp that goes for a week. I ended up on this week-long bootcamp with thirteen men competing for a job that I didn’t particularly want, and then they offered me the job. I thought, “I’d rather regret what I did than regret what I didn’t do.” I ended up being caught by accident. I never thought to get there, but I thought what an amazing opportunity. I’m going to have a crack at this. Lo and behold, it opened and ended up living there for a year.

Be careful what you wish for. Sometimes you get it but it’s such a cool thing though. It’s like if you knew how hard something was going to be, would you have even done it? You probably don’t want to know like when you start your own company or do other things. Looking back, you go, “I’m glad I didn’t know that.” I’m sure you’ve learned some amazing lessons. You talked about Respect Trumps Harmony, your book. I’m sure you learned a lot of the lessons from what you’ve gone through. I want to start with what is it like in Antarctica, first of all? I can’t even imagine. I live in Arizona. It’s a slightly different climate here.

It’s funny, not many people on the planet would get a feeling for what it’s like to live in lockdown in isolation for a year. Given this pandemic, most of us now have a little insight into what it’s like to be locked into a place and locked down in isolation. The environment is harsh. It’s minus 32 degrees. It’s months of darkness. You can’t get in or out in winter. You stuck with people that you may not like that you didn’t get to choose. The environment is one thing but it’s the intensity of being in lockdown with seventeen other people with no privacy. The interpersonal pressure of living there is hard often, much harder than the environment. I coped with the environment because I expected it to be tough, but living with seventeen other adults, you can’t get away from them. I’m switched on 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for a year. People stuff and the living stuff was way harder than the environment.

I would imagine and I panic a little bit when I hear that. A little bit of claustrophobia kicks in with me. I remember when I hiked out of the Grand Canyon, we did river rafting and did all that first. You think what happens if you get sick or something happens. One guy got sick in our group. A helicopter was there in five seconds and he’s gone, they take him away. What happens if you get sick down there in Antarctica?

It’s diabolical because we can’t get in or out. There was an incident a few years ago where the American doctor, Dr. Jerri Nielsen, was diagnosed with breast cancer down there and had to stop. They did the biopsy and started the chemotherapy on herself using a mirror because they can’t get out in the middle of winter. The thing we aim for down there is to not get sick and not get injured in the first place. We screen people. We do a lot of medical screening and health screening before we go. The bottom line is when we’re down there, we try to keep safe and not get injured because we can’t come home, we can’t get out.

Respect Trumps Harmony: Why Being Liked is Overrated and Constructive Conflict Gets Results

The other thing with my team was we had a professional doctor at the station but we didn’t have emergency services. My carpenter went and did two weeks of training at a hospital to become the business. My IT officer did two weeks of training to become an anesthetic assistant. That played around emergency response. The idea is not to get injured in the first place because it’s serious. It’s diabolical. It’s a tough place to live.

That would be scary. Thinking of my little silly hike out of the Grand Canyon thing, when that guy got sick, all the people that were on this trip who were there, a lot of them were doctors. When the guy said he didn’t feel well, they’re all ripping drugs out of their bags. You could see ten people went into their bags for medications. When you don’t have a lot of doctors and all they have is two weeks’ training, that’s a little frightening. You’re in that setting, you’re also dealing with food and sleep issues. Are you able to sleep? Did you have peace and quiet at all? What was the food situation? Those kinds of things always interest me.

The sleeping is interesting because in winter, it’s 24 hours of darkness. Summer is October through until March. We go out in summer. It’s 24-hour daylight. That’s a lot harder to sleep when it’s daylight because you get a little sliver of light comes through the curtain and your brain wakes up and says, “It’s morning, wake up.” That’s a lot harder to sleep than in 24 hours of darkness. The food was great and I can’t criticize it. We have a full-time professional chef who cooks our meals. The downside is all of the food is processed.

It’s all frozen, packaged, dehydrated food. Things like pizza and pasta and a roast dinner. It was okay but anyone who’s been through a lockdown can relate to this, the challenging part is you don’t have a choice. You might be thinking, “I feel like a bit of grilled chicken and salad for dinner.” You go down to the dining room to have curry or pasta. You have to get what you get. Whatever the chef has cooked, that’s what you’re eating. That was a big issue, the lack of choice. What I felt like eating that night was not what I was going to eat because the chef hadn’t cooked it. You have to eat whatever the chef has prepared for you. It’s good food but it’s processed. There’s no fresh food. We can’t grow vegetables down there, even fruit. When I got back to Australia after a year down there, I was craving for fresh fruit. I wanted an apple.

Something normal. I can imagine that would be hard. What did you do all day? What were you there to do?

It’s a different place in summer and winter this time of year in all of the stations around Antarctica. Around October, November, our scientists arrive. We’re doing climate change research. We’re doing global warming research. That’s the only reason we’re there. At this time of year, all of the scientists will come in easily by helicopters and planes. I had 120 people on my station over the summer so it’s fun, but then they go home in February and a little group of eighteen of us stay behind. The eighteen of us which are there for asset management and maintenance.

We have to maintain the station and keep it warm, keep it running until the next summer when the next group of scientists arrive. Winter is different because it’s dark and it’s boring. There’s only a little core group of people. Summer is a lot more around management, managing resources and getting a program delivered on time on budget. Winter is a lot more around that leadership, morale, keeping people motivated and inspired through a difficult time. It’s quite different in summer and winter. It’s a weird place.

It would be different. Climate change is an interesting thing. I know you have an MBA. What was your undergrad in? Do you have a science background?

My undergrad is in journalism. I started off in journalism and public relations. I started off on my first career and I’ve got a job in journalism and public relations. I thought, “This is not what I thought it would be.” I thought I would love this but I don’t. I thought I would enjoy it. I was working with an environmental management agency. The park rangers would come into the office every day and they were happy. I thought, “I want to be happy. I want to be like you.” I want to get out of bed in the morning and go, “Yay.” I decided I’d be a park ranger. For the next sixteen years, I was a park ranger and then I became a chief ranger.

Respect Trumps Harmony: You didn’t have to worry about your colleagues complaining about you behind your back, because if they had something to say to you, they’d come directly to you.

I’m sure many of you will have heard about the Great Ocean Road. I was the Chief Ranger of the Great Ocean Road in Australia. That beautiful place with the Twelve Apostles and the limestone caves. I have group down there. When I went to the Antarctica, I wasn’t running away from that horrible job. I had this extraordinary job where I was managing one of the most beautiful parts of our country. I loved it but it was such a great opportunity. When I was offered the role in Antarctica, I said, “What a great opportunity to experience a place that not many people get to.”

The wildlife is amazing. The Aurora Australis, the Southern Lights is beautiful. It’s stunning. The hard part was that it was a workplace. I’m managing a team and it’s a workplace so we had to work. On a holiday, it would be a different scenario but it’s an extraordinary place. I did believe I’d rather regret what I did than regret what I didn’t do. No matter how hard it got, I’d rather be there and go, “What have I done?” than not do it and spend the rest of my life wondering, “What if I’ve done it?” You get the opportunity.

You’ve got these eighteen people, are they all men?

We had a crazy team. We had fourteen men and four women which is unheard of. It hadn’t happened before and it hasn’t happened since. Every year, it’s been all men.

Were any of them couples? Did everybody not know each other?

We hadn’t met before. It’s not unusual for a couple to go down there. In my particular team, we met each other for the first time when we arrived for our three months of training. I didn’t recruit the team. I had no input to the recruitment and we all rocked up, turned up, and met each other for the first time in training. That was extraordinary to look a bit and think, “I will spend a year of my life with you and no one else. I’m meeting you now for the first time.” It’s intense.

Did anybody ended up as a couple after that?

My chef went back two years later and met her now-husband. It was funny when she got married. She got married on a Wednesday. I remember thinking who gets married on a Wednesday? Why would you get married on the week and not on the weekend so everyone can come up? When I saw the date. The date was the 21st of June, which is the winter solstice, and it’s an important date in Antarctic history. Even now, it’s our only public holiday down there for most of the stations. It’s a big, significant day for Antarctica. When I realized the 21st of June. They couldn’t get married on any other day.

When you talk about putting all these people together, it reminds me when I had Amy Edmondson on the show who’s a Harvard professor. She did a great TED Talk about how they rescued all the Chilean miners from underneath the rock, and how everybody had to get together and work together. They didn’t know each other until that point. They had to all cooperate and use curiosity to do this collaboration. You had eighteen random strangers and you had to turn them into a team. I’m curious how you did that. What issues did you run into?

Respect Trumps Harmony: Getting irritated about small things is often a symptom of a deeper issue: lack of respect.

It was challenging because all the Australians particularly on the Australian Station, there’s a real culture of mateship. We’re all mates. I recognize the diversity. I recognize how different we were across gender, religion, culture, personality types, professions, age, generation. After a while, we are different that we won’t always see eye-to-eye. I took that off the table and I said, “I don’t expect you all to love each other. I don’t expect you all to even like each other but I do expect that you will treat each other with respect.” Our mantra was respect trumps harmony. That simply meant that we don’t have to agree and love each other all the time, but we will treat each other with respect.

The most important tool that we used was a thing called no triangles. No triangles was simply I didn’t complain to you about Diane. If I had something to say to Diane, I’d go directly to her. I don’t take it to a third-party. That little simple rule of no triangles meant that in a difficult environment, in a difficult situation, we’re trying to cope and do the best you can. You didn’t have to worry about your colleagues complaining about you behind your back. If they had something to say to you, they’d come directly to you.

That simple tool built so much respect in the team. My role as a leader was to create that culture and that environment where people could speak up because a year is a long time to be in that environment. Honestly, I don’t think you can suppress those emotions and feelings for a year. It’s difficult to hide how you’re feeling in that intensity for an entire year. I went the other way of how do we create a place and a space where it’s safe to speak up. Respect trumps harmony became the rule. It meant we don’t have to agree but we will always treat each other respectfully.

That’s so important and I love the no triangle thing. It’s interesting because I’ve seen that in a lot of women relationships that if there are three women, you end up having two of them talking, and then one gets left out sometimes. I don’t know if men, I’ve never looked on the research on this but this is my personal thing, I’ve noticed that sometimes happens. I love that idea that you don’t allow that. That’s a problem I’ve seen in a lot of workplaces. There’s somebody who always feels a little bit left out. When you were talking about how we all can look at each other and respect each other, it ties a little bit into my work in perception.

What I was looking at was the process of how we make decisions, how we respect one another and look at other people’s perception of things. We don’t all see things the same. I saw it as a combination of IQ, EQ for Emotional Quotient, CQ for Curiosity Question, and CQ for Cultural Question. It puts us all together into this process that I call an EPIC process. It’s this process where you Evaluate, Predict, Interpret, and eventually come to this Conclusion. You have to have all this data about each other. Anytime you talk about teams, the forming, storming type things. How long did it take you guys to feel like you were in the groove of a team?

I would say a solid 2 or 3 months to feel like a team. It took a long time. One of the challenges was we had what I call the Bacon War. The Bacon War is not a metaphor. It start with the bacon. Should it be cooked soft or crispy? It goes back to your perception. When I got to the bottom of it, when I asked the five whys and I tried to get to the root cause, I found out that one team thought the other team was deliberately cooking the bacon in the opposite way. They prefer it soft and the other team is cooking it crispy. They thought they were doing it deliberately.

Their perception was that the other team was deliberately trying to antagonize or irritate them. I thought this is not about the bacon. It’s manifested in the bacon but they’re feeling disrespected. They’re feeling like they’re not heard. I started to identify all of these little things that were happening with the team that were symptoms of a deeper issue. The deeper issue was that lack of respect. Ever since, I keep my eyes open nowadays and even working from home, all of us at home or at work, there’s these little things that irritate and drive us crazy and it’s all such small things.

Often, it’s a symptom of that deeper issue, and the deeper issue is the lack of respect. We know someone who’s always late and we thought that’s just him or that’s just her. I’ll say that’s disrespectful. If everybody else can get to somewhere on time, you can too. It was eye-opening for me because I couldn’t understand why little things would drive me crazy and drive other people crazy. It was this epiphany that dropped for me that it was a deeper issue, it was the lack of respect and it all came down to the bacon.

It’s always something else when it comes to any fight like that. It’s a challenge when you’re locked up like this. When I first saw your information, I didn’t know if you had done any exercise-related thing having to go from one area to another because I saw there were three stations in Antarctica. Was there any exertional thing involved in this? Was this all inside work that you guys were doing? I’m trying to visualize this.

[bctt tweet=”We don’t have to agree with each other all the time, but we must treat each other with respect.” via=”no”]It’s mostly inside work. You can choose. It’s optional. If you wanted to go outside, by all means, you can go outside. Generally speaking, you can think of an average high school with outbuildings and walk from one building to the next building. That’s what it’s like. It’s a tiny little community. The interesting part is that we have several different jobs or roles. We have our professional role that were slightly different than the Americans. The larger American stations have hospitality staff but the smaller stations don’t have hospitality.

We have to clean the pass out. We have to clean the bathrooms, windows, walk down tables, all of us have to chip in and help as a community. We also have all of the other roles. We even have to vote. Anyone in Antarctica is expected particularly Australian stations. We legally have to vote that the others have an option to vote even during an election. We have someone who collects the ballot and send them off. We have someone who puts the flag up the flag pole on a special day. We have a post office which is open for one day a year where someone has to stamp the envelope.

We get mail from all around the world and somebody has to stamp to give it that mark of Davis Station in Antarctica for the people who collect stamps. Any role that you have in a normal community, particularly a smaller rural community where everybody takes on volunteer roles, that’s what we had to do. We had to have our professional job but we also had to chip in and help out. That meant things like firefighting, search and rescue, all of that. Somebody has to put their hand up and take on the role of a firefighter or search and rescue person. It was an extraordinary place.

I’m trying to figure out your job-job in addition to all these other jobs because you said you’re there working on climate change. Are you dealing with paperwork? What are you doing as part of what you’re doing during the day? I can’t visualize that part of it.

That was the tough part for me as the leader. The rest of the team are tradespeople. We’ve got a plumber, electrician, carpenter and it’s obvious what they do. They keep the power, they maintain the water, they keep the place running. For me, as the leader, the difficult part was the vast majority of my time in winter was spent counseling people or talking to people and trying to support them and help them. When I did turn up for lunch and walked into the dining room at lunchtime and people said, “How’s it going, Rachael? How’s your day been? What have you been up to?” I couldn’t reveal what I had been doing because of privacy reasons. I couldn’t turn around and say, “I’ve spent three hours talking to someone on how their feeling.”

I’m worried about the mental health of someone. I’ve spent a few hours trying to support them and get them the help that they need. I couldn’t reveal that. I couldn’t talk about that. The vast majority of the work I did, which was around keeping the team inspired and keeping morale up, I couldn’t even share that. I couldn’t tell about that. Summer was different. Summer was all report writing because we’ve got a massive program of science projects as well as construction work. We do a lot of construction on the station in summer. Every day, I’m reporting back to head office on how we’re going and delivering these projects. In winter, most of my work was below the shift. It was all of the human stuff, supporting people and helping people.

I’m envisioning this and in my mind, I’m seeing the Big Bang Theory episode where they all got locked in together. Was it anything like that where you’re like, “We’re here.” You get frustrated. I’m thinking, do you have weekends off or time off? If you do, what do you do if you’re stuck there?

In summer, it’s different. In summer we work every day because we’ve only got this little window of opportunity to fly out to a place and do our science. If someone’s doing penguin biology so they’re studying the penguins, they need to go and get a blood sample from the penguins. They can only do that in summer because we can only fly aircraft in summer. We fly them out to the penguin colony. They’ll observe the penguins and whatever they need to do. In summer, we work every day because we’ve only got this brief 6 or 8 weeks where we can get outside and do science every day. Winter, we tend to work Monday to Friday from 8:00 until 4:00, and then Saturday morning is set aside.

That’s for our community. That’s the time where we empty rubbish bins, get the vacuum cleaner out, do the carpets or clean the windows. Saturday afternoon, we have off and then we don’t work. Sunday is the rest day. Saturday night in winter is our formal dinner, which means we put up linen tablecloths and the men might have a shave, the women may put on some lipstick. That’s our formal dinner. That’s the only time when the community is expected to get together as a team. The chef will cook a themed dinner. It might be a Greek dinner, Italian or Mexican, whatever. We live for it. It’s exciting. The Saturday night is absolutely wonderful when you’re doing the same thing. The challenge in winter is it’s Groundhog Day. It’s the same thing day-after-day.

Respect Trumps Harmony: It really is a place for grownups because you have to take responsibility not only for yourself and your safety, but also your own mental health.

A lot of people are feeling like that with COVID. It’s the same in a sense. Did you get to go see the penguins? Did you get outside? Is it too cold? I don’t even know how cold it gets there. I’ve been to Alaska, it was cold enough there. I have no idea what the difference would be if you went to Antarctica. Can you get outside and do things in the summer without wanting to shoot yourself because it’s cold there? What is it like?

You can. The stations are around the edge of the continent. They’re on the coastal areas which are a little bit more forgiving than the middle of the continent. It’s around minus 32 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s the coldest we got to. We try to get outside as much as we can. Everyone through this pandemic will have an insight into what that’s like in winter. What it’s like to be with the same people doing the same thing. The important thing for us down there certainly during the pandemic is to celebrate those little short-term wins. What we did in Antarctica is we celebrate small things like 100 days without power blackouts or 50 days without our Arctic server crashing.

It was to build momentum, take these moments, and create this theme that we’re still moving forward. We’re still achieving. We’re doing okay. I’ve been doing that now in the pandemic because I’m in Melbourne in Australia and we’re in lockdown again. We’ve been in lockdown and the curfew has been lifted. We’re only allowed outside for two hours a day and that’s only for exercise, medical care or shopping. It’s a strict lockdown and I’ve be talking to all of my community and my friends here saying it’s so important that we celebrate these small wins along the way.

Celebrate a birthday, an anniversary, make a cake, buy your stuff a cake, open a bottle of champagne, or do something to celebrate these little wins. You get that same sense. We’re still moving forward. We’re not spinning our wheels. It’s not Groundhog Day. Mentally, for us in Antarctica, that was important to keep that sense that we’re getting closer to the finish line. We will go home one day. The expedition will be over and we’ll get to come home. It’s important.

You say that and that reminds me, you knew it was going to be over in a year. No one knows when this is going to be over. Did it help you to know that there was a time limit? I would imagine then it gets back to normal. That’s a big challenge. As you were saying that with the power thing, now I’m starting to think, what if it was a 24-hour dark day winter and your power goes out, what do you do? I get right to the panic part in my mind.

That is so astute because the power going out is significant. It’s deadly because the electricity keeps the station warm. It keeps the heaters and also stops the water from freezing because you can imagine if you’ve got water going through a pipe at minus 32 degrees Fahrenheit, it will freeze no matter where’s that water is cased in, whether it’s copper or plastic, it will freeze. We need to put a little bit of power going through the pipe to heat the water so it doesn’t freeze. When we lose power, it’s difficult because we’ve got scientific instruments going the whole time.

That’s one issue if the power goes out. The data stops being collected and that’s one issue. In terms of human life, if we don’t have that power going then we don’t have heating, water and sanitation. It’s a significant issue if we ever lose power. We jumped on that straight away. We have a little pager that the electricians wear little pager on their pocket and they get an alarm that goes out and says, “There’s something going on with the power.” You’ve nailed it but that’s a significant issue. Back here at home, if the power goes out, it’s a bit irritating and annoying but down there, it’s life and death.

There’s always that sense that you think you’re in control in most situations. If something went wrong, how long would it take for somebody to get to you?

In summer, we could get someone there in about two weeks, maybe a week. In winter, you’re talking months because we can’t get to the other stations. The American Station is on the Peninsula right near South America. That 2 or 3 days sailing or a couple of hours flight from South America into the US station, but the Australian stations were right on the other side. Even for us to traverse that whole continent whether it’s by vehicle or flying, that would be days, weeks, and months on land. We don’t have a landing strip. We don’t have an airport for a big plane so we have to use little planes, and they need to be refueled every couple of 100 miles. It’s a huge logistics exercise to evacuate someone in the middle of winter. In fact, it’s impossible during the middle of winter.

[bctt tweet=”Learn to celebrate short-term wins along the way.” via=”no”]It’s a tough place and it makes you stop and think about in terms of safety. Rather than me as the leader telling my team you can’t do this, you can’t do that. I said to them, “If you think it’s an unsafe thing to do, it’s because we’re a long way from help. We are nine months away from the nearest hospital so you manage your own safety and you manage yourself.” It is a place for grown-ups because you have to take responsibility for yourself and your safety, but also your own mental health. They need to be self-aware enough to understand, “I’m struggling today. I’m not feeling myself today.” Intervene on yourself and do something about that because mental health is a big challenge down there.

What did your parents think of you doing this?

When I rang my parents and I said, “I’ve got this crazy job. I’m working overseas. We are at Antarctica.” They said, “How often will you come home?” I said, “I can’t. We can’t come home.” They said, “Can we come and visit?” I said, “No, you can’t get in or out for a year. You can’t get out of the place.” They’re a little bit standoffish and cool about it. I was disappointed. I thought, “I’m the second woman to get this job. That’s significant. I thought you’d be proud of me.” When I became a mom, when I had my son and I was a mother myself, I recognized, “I’m their only child.” Even though I was 35 years old at that time, I’m still their child. I understand it now.

My child did the same thing and I was feeling the same way. You can’t get to them if they need you. They came around. Now they’re proud. They’ve got scrapbooks of newspaper clippings of me whenever there’s been a story. They’re proud of me which is gorgeous. I hadn’t planned it. It started with this opportunity that came my way. I thought, “I’ll have a crack at this.” I never expected to get the job. I wasn’t talking about it since I was a little girl. It’s not like the Olympians or the elite athletes. For years, I plan it and I train for it. From there, it was an out of the blue opportunity. To have to tell all my family and friends, they’re like, “What?” They kept saying, “Why?” I kept saying, “Why not?”

I could see why but it would be terrifying at the same time. I’d like to push myself to do something that is not your norm that makes you feel a little uncomfortable because if you feel like you’re living instead of existing sometimes if you go beyond. I’ve had a lot of people on the show from Saray Khumalo, Erik Weihenmeyer, Cathy O’Dowd, they’re some of the people who’ve hiked and climbed these mountains, Everest, and all the things that they’ve done. It pushes you to the next level of something that you wouldn’t think of doing. I’m curious on the communication aspect, how do you communicate? Are there phones? How do get in contact with the outside world from there?

We have emails so we’ve got a satellite. We have the internet. We have a telephone but the interesting aspect for me was that we don’t have television or video conferencing. We’ve got no media and no media coverage. I’ve been talking to the team who were down there at the moment. They’re aware of the pandemic and COVID-19, but they don’t understand the impact it’s had on every aspect of their lives, our work, our finances, our health, all of those different things. For them, it’s a concept because they’re not living it all the time, and there’s no media coverage. They’re not switching on the television and watching the news, listening to a podcast, turning on the radio and listening to the news, and the latest update around the pandemic.

This shielded and protected in a way that they can choose to have no involvement or understanding because they haven’t got any media coverage, no newspapers, nothing like that. They can choose to read online news, but if you choose not to, if you say, “The only way I can cope with this place is to live in this place and exist in this little place. I don’t care what’s happening in the rest of the world because it doesn’t have any impact on me.” You can live quite happily down there with no knowledge of what’s going on in the world. It’s funny with pop culture, music and movies. I’ve got a whole gap in my understanding of movies and songs. Everyone is singing this song which was top of the Billboard Charts.

Everyone was singing all these amazing songs that everyone knew the words to every song. I’m like, “I had never heard this song before. I don’t know this movie.” The movie that won the Academy Award that year and everyone said, “You must have seen that movie.” I’m like, “No. I don’t even know what you’re talking about.” Even in terms of pop culture, this whole gap for a year where I don’t know what books were released that year, I don’t know what movies came out because I was existing in this little place down the bottom of the planet with my little community. I had no access to that stuff.

As you say all that, I wonder how much your life did change when you come back. You miss a year. Now you have the shock of getting back to doing things in a way that you weren’t doing them for the last year. How long did it take you to feel normal?

Respect Trumps Harmony: It’s almost like a trauma. They just need to put it behind them and get on with their life.

I estimate about 4 or 5 months to come back to normal. It was a long time. I’m talking to people now. We’re in lockdown in Melbourne and starting to get people prepared for what it will feel like coming out of lockdown. When I came home from Antarctica, I assumed that I would be excited and happy to be home and everything would slip right back in. I was excited but the biggest feeling of all was overwhelmed. I was overwhelmed by noise and choice. Suddenly, having these choices about what to do on the weekend. I was overwhelmed by everything. It was totally unexpected because I thought I would slip straight back into life. What I did and I also talked to experts who work around the world and I tell them when he come home for a visit, don’t post that on social media.

The most important thing when you get home is to reconnect with the people who are most important to you. That’s what I did. I reconnected with my family and friends. I didn’t tell the broader social community that I was home for about a month because I knew what would happen. I knew that that they would be excited and then say, “Come around to my house and we’ll have dinner. You can show me your photos.” After a year of living with a tiny little team of people, being back with tons of people who’ve wanted to give you a cuddle and a hug. I had no physical contact for a year, suddenly people want to hold me and everyone wants to see me in a short while.

I had to protect myself a little bit and be quite strategic around how I re-entered society because it’s such a shock. I can see it all around the world now with people coming out of lockdown. I worry that people might think that they will return to normal straightaway because some people might. I think there will be a whole group of people that will struggle with that re-integration back into the world and particularly around public transport in hotspots. People have to get on a train or a bus and they’re in a hotspot. That anxiety around is it safe to do that? Is it okay to do that? That will be a real challenge for lots of people.

It does change you. I’ve had meningitis. I remember before that, I never thought at all about holding rails as you’re going up an escalator. You don’t think about touching anything, but you get that sick and you start thinking about things. I didn’t become a germaphobe but I got to the point where I think about things where I never would have in the past. It’s such a different experience that it changes you. Everybody will be a little bit different of what they want to touch. Even when I hike, my husband and I still do a lot of hiking because they’ll let you out here to do things like that in Arizona. You think about, do you want to touch that rock? Who was touching that rock? It’s something you never thought of.

I fly a lot for work. I fly around the world and I spend a lot of time in airport lounges, in the lounge area. They have a buffet, nice food, and you can help yourself to the smorgasbord of food. I pick up the utensils and the tongs to pick up the food. It’s only now that I’m thinking, “Thousands of hands touched that before me.” It has changed me because I won’t do that ever again since things that weren’t even on my radar had not even thought about. It’s not a germaphobe but it’s a consciousness that I didn’t have before around how many other people have touched this item that I’m about to pick up. It will change it. The big important message for me is to understand that because someone else might be perfectly fine with that. They’ll live with it and they’ll get fine. I’ll get back into it and pick up the tongs and the side service, and they get on with it. It’s going to be people like me going, “I can’t do that.” It’s important to have that empathy and we will all react differently.

It’s going to be a strange world. I used to be a pharmaceutical rep and sold antibiotics. You want to have a certain amount of normal flora. You want certain things in your body, bugs because it’s good for you. There are good bugs and bad bugs. If you’re shielding yourself from everything, you wonder what the impact is going to be for all this. This is all such a crazy time.

There’s an impact. In Antarctica, we don’t have bugs and germs. Two things, they can’t survive those temperatures. We don’t have people introducing bugs, virus or germs. We’re healthy down there because there’s no virus, bugs or germs. The difficulty is when you come home, when you get back to the real world. When I got back, I had a cough. I was coughing for about 3 or 4 months. It wasn’t that I was sick. It was that my immune system had gone asleep.

My immune system had been repressed for twelve months because it wasn’t needed. I didn’t need an immune system down there. When I came back, I picked up every virus going around. That was not in the brochure. I did not expect that to happen. No one talked about it, no one warned us or mentioned that this might happen. It was one of those things. The physiological impact on your body of living in Antarctica is extraordinary. Nothing prepared me for it and nothing prepared me for coming home and thinking, “I’m going to have to deal with this now and rebuild my immune system.”

If they told you everything, they wouldn’t probably get anybody to do it. That’s the problem. I’m curious, did you remain friends with any of the team? What happens when you get that close with people and then all of a sudden you go off on your own? Do those relationships last?

[bctt tweet=”Sometimes, you’ve got to yourself to do something out of the norm to feel like you’re living instead of just existing.” via=”no”]When I was down there as their leader, I wasn’t friends with any of them because I felt like I needed to have that arm flanked relationship with all of them. I couldn’t be friends with Simon and not friends with Alvin. I was friendly but I wouldn’t classify any of them as my friends while I was down there. When I got back, when the power relationship was not there anymore, when I wasn’t the leader, I became good friends with about 4 or 5 of them. I’m still to this day good friends with five of them. There’s another little cohort that I’m friends on Facebook. If I wanted to get in touch with them, I could.

There’s a group of about four of them that if I’d never seen them again for the rest of my life, I’ll be happy. Some of them are difficult to live with and hard to manage because you’ve got no sanctions or reward, even in terms of performance management because it is a workplace. In terms of someone who isn’t performing their job, I can’t kick them out. I can’t give them a letter of warning. I can’t back them so I had to try and manage their performance in other ways. It was a difficult situation. I’m more than happy that I have not seen them with regards to that. There are lifelong friendships. The interesting thing for me was when we arrived back home after a year. It takes two weeks on a ship for us to get back to Australia, two weeks on an ice breaker.

When we arrived back in Australia, some of my team grabbed their family, friends, suitcases, then took off. They did not even say goodbye. I always found that extraordinary. I asked the psychologist and I said, “What is that?” You’d think after a year of living together when at least we see each other a lot, enjoy life, have a great life. They just took off. I said, “What’s that about?” The psychologist said to me, “It’s such an extreme situation that they want to put it behind them. It’s almost like a trauma. They need to put it behind them and get on with their life.” It’s interesting. It’s not just myself, but the rest of the team has not heard from these people ever since. There are some who coped well but there’s certainly a little cohort of about four of my team who did not cope at all. When we got home, they wrapped their arms around their family and they took off. I respect that. We all had a different experience at the other end differently. I can’t say that it was a positive experience for the whole team because I know it wasn’t.

If you have PTSD as a potential from your job, was it a pay good for something like that kind of a job?

It’s extremely well-paid. It has to be well-paid because people wouldn’t do it otherwise. That’s the issue. A lot of people think that it’s a fast way to save a deposit for a house. I can save $100,000 or $200,000 fast in a year and get a deposit for a house. For some people, that’s the motivator that don’t look at the other side of the cost. That’s the benefits. What’s the cost? The cost is you’ll be away from the people that you love. You’ll be away from all of the things that keep you resilient whether it’s going to church, walking on the beach, walking a dog, watching sport, whatever you do to keep yourself resilient is gone.

I don’t think enough of my team reflected on that bit. They looked at the benefit. I don’t think they reflected enough on the cost of having to give up every single thing that you love, you have to give up for a year. If anybody contacts me now and says, “Can you give me some ideas of what it’s like?” That’s certainly one of the things I’ll pick up, that you’ll give up everything you love and you need to be prepared for that because it’s hard to imagine living without your family and friends for twelve months but that’s what you do.

That’s got to be tough. You come back and then you think the next job is going to seem boring maybe, but yours isn’t because you’re an international keynote speaker now. You’ve presented over 1,200 conferences around the world. Did you do that right off the bat? Did you start speaking? What was your next job? Was it boring?

I went back to being a park ranger and my CEO one day asked me, “Could you do a presentation for a charity?” He was also the chairman for a children’s charity and it was a fundraiser. I said, “I can do a little presentation for your fundraiser.” I did one presentation. In the audience that day, there happened to be a gentleman from Speaker Bureau. I didn’t even know what Speaker Bureau was. I’ve never heard of Speaker Bureau. He approached me and he said, “Would you like to do more of that?” I said, “What?” “Tell that story.”

He said, “There’s not enough leadership based in Australia. Most of our leadership here are academics when they start leadership. There are few women who talk about leadership.” I’m like, “Okay.” I started speaking at Breakfast A Minute. I was working full-time during the day and it took off. It went crazy. The phone is ringing. People are saying, “Come and talk to this group.” That was another pivotal moment where I had to say, “Do I give up a paid job, paid employment, and start my own business speaking about leadership?” I thought about it for months. In the end, I took that leap of faith. I thought I’m going to do this. Even now in lockdown, I’ve got my own studio. I’m working virtually in Denver and in Seattle.

Sometimes, you’ve got to yourself to do something out of the norm to feel like you’re living instead of just existing.

You’ve got your new book and your last book Leading On The Edge. It’s great. It’s under option for film or TV, right?

Yes. It comes full circle, it goes back to the opportunity of seeing a little tiny advertisement one day in a newspaper. It’s extraordinary how life have its sliding doors moment that if I did not see that little advertisement, I wouldn’t be talking to you. My whole life would have been completely different.

It’s your curiosity. You were curious enough to find out. Would you change it? Are you glad you did it?

I wouldn’t do it again. Anyone who’s been in a leadership role will know the scrutiny that you’re under as a leader, and that’s normal for any job and any household, as a parent, you’re a leader. To do it in a workplace for 24 hours a day, 7 days a week for a year with the whole team watching you so there was not one second. I could take off the leadership hat and say, “I’m not going to be the leader now. I’m going to have a day off.” There’s no way. The scrutiny was too much for me to do it again. I don’t regret it for one second. It’s a tough one. If I knew then what I know now, would I do it? I would probably still do it again but I don’t regret it, but I wouldn’t do it again. It’s tough to be a leader.

One time, you’ve paid your dues and you learned some amazing things from it. All the insights you’re giving people now of what they’re going to have to deal with COVID and everything is inspiring. A lot of people would want to read your books and see your film when it comes out if it comes out. Is there some way they can follow you or learn more about you? Can you share a link?

They can jump on my website which is my name, RachaelRobertson.com. I’d love to speak to anyone. If anyone got questions, interested in Antarctica, or they’d like me to come and speak to their team, school or community virtually here in Melbourne, I would love to hear from people. I would love to answer any questions that people have.

This is an amazing story, Rachael. Thank you for sharing. It’s unique. I’ve had a lot of different, cool things that people have done but this was completely different. I was looking forward to this and I give you credit because I don’t know if I could have handle that for a year. That’s a tough gig but you’ve learned some amazing lessons and I enjoyed your story.

Thank you for having me and thank you for the opportunity to chat.

You’re welcome. This was fun.

—

I’d like to thank Rachael for being my guest. We get many great guests on the show. If you’ve missed any past episodes, you can find them at DrDianeHamilton.com. There’s more than 1,000 people I’ve interviewed on the show. There’s plenty to catch up on if you’ve missed it. I hope you enjoyed this episode. I hope you join us for the next episode of Take The Lead Radio.

Important Links:

- Rachael Robertson

- Leading On The Edge

- Respect Trumps Harmony: Why Being Liked Is Overrated And Constructive Conflict Gets Results

- Amy Edmondson – Previous episode

- Saray Khumalo – Previous episode

- Erik Weihenmayer – Previous episode

- Cathy O’Dowd – Previous episode

About Rachael Robertson

After 15 years leading diverse and remote teams and business units, I took the jump and lead the 58th annual expedition to the edge of the world: Antarctica. It was a tough, gruelling and exhausting year, but ultimately extremely rewarding and fruitful.

The intensity of this leadership role, where the leader is on-duty all day, every day, for 12 months with no respite, gave me the opportunity to road test my leadership ideas the hard way – without the luxury of peers, a desk or high-speed broadband! It was a “leadership laboratory” in the most extreme, hostile environment on Earth.

I present real leadership. Real stories and real insights – the highs and lows and the ups and downs of being an authentic leader.

My work is in response to a massively growing demand in the business world to get real, practical tools backed up by solid theory from someone who has actually led, and led successfully.

-

So, how do you lead diverse teams that seem to have no obvious common ground?

-

How do you motivate people to do the really hard tasks?

-

What happens when a crisis occurs and all eyes are on you?

I draw on incredible and often hilarious examples of what authentic leadership looks like, in a world where most classic leadership theory doesn’t apply .

Since returning from Antarctica, I have spoken at over 1500 national and international conferences and events with clients drawn from all industries and sectors including mining, pharmaceutical, construction, health, education, finance, hospitality and retail.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

0 Comments