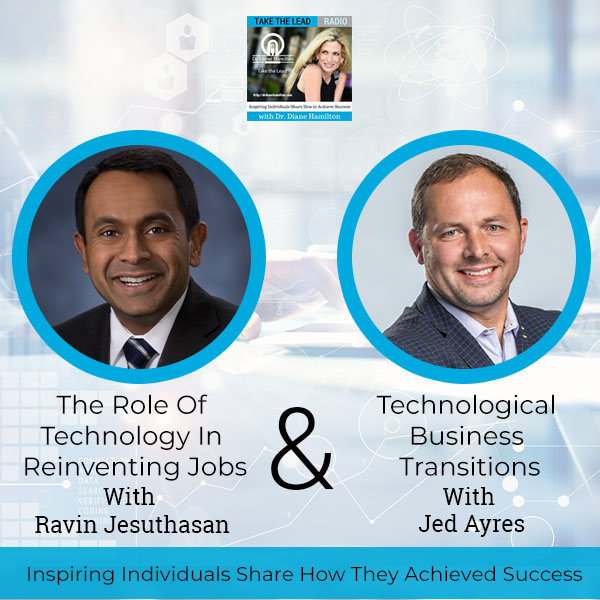

In this day and age, technology keeps on rising to new levels with constant innovations. Technology has also taken extraordinary steps into the world of business by reinventing jobs. In today’s episode, Ravin Jesuthasan talks about how technology is reinventing the jobs we have known for a long time. Ravin is a recognized global thought leader, futurist, and the co-author of the book Reinventing Jobs: A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work. Listen in as Ravin joins Dr. Diane Hamilton to discuss technology’s role in business.

Business covers a lot of areas that need attention, especially when you are aiming to scale your business as an owner. One of these areas where technology has been incorporated to help produce better results is marketing. Jed Ayres talks about how marketing has been improved by innovations of technology. Jed is IGEL’s Global CEO, a company aimed at providing next-gen operating systems and endpoint security, optimization, and control solutions for cloud workspaces and virtual desktops. He joins Dr. Diane Hamilton on today’s podcast in a conversation about technology, sales, and marketing.

We have Ravin Jesuthasan and Jed Ayres here. Ravin is a global thought leader, futurist, and author regarding the future of work and human capital. Jed is IGEL’s Global CEO. He helped simplify it and secure the cloud delivery of applications and resources. We’re going to talk a lot about ways to lead in the future and some technology. It’s going to be fascinating.

Watch the episode here:

Listen to the podcast here

The Role Of Technology In Reinventing Jobs With Ravin Jesuthasan

I am here with Ravin Jesuthasan, who is recognized as a global thought leader, futurist, and author on the future of work in human capital. He has led multiple research efforts on the global workforce, the emerging digital economy, the rise of AI, and the transformation of work. He has numerous research projects for the World Economic Forum. He is a regular participant there. He’s also nominated to Thinkers50 Radar Class Of 2020. It’s nice to have you here, Ravin.

Thank you, Diane. It’s great to be with you.

I was looking forward to this. You have an impressive background. I know you do a lot of work with HBR and all the things that you’re working on. Before we get into some of that, I’d like to get a background on you. What lead you to this point in your life? Can you give me your bio?

I’ve had the privilege of doing a number of different things over the course of my career. I am a retreaded finance guy and was a strategy consultant before I came into this interesting world of human capital and work. I joined an outstanding organization many years ago. Through all of its changes, through all of the opportunities it’s provided, I have stayed on. I joined Towers Perrin back in 1994. Towers Perrin became Towers Watson, which became Willis Towers Watson. Over the course of those years, I’ve had the privilege of perpetually reinventing myself. Taking on new roles and new responsibilities. When you get a little older, like I am, you have the privilege of being able to choose your clients. I get to choose some of the most complex, most interesting, most global organizations where I feel I can make a difference.

I know you’re listed as one of the 25 most influential consultants in the world. That’s an accomplishment. I think that what you’ve worked on is cutting edge or you don’t get nominated by Thinkers50. I’m curious, you have co-authored a book with John Boudreau, Reinventing Jobs: A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work. I want to know a little bit about this. Is this something you did for HBR and what led to this?

The road to this has been interesting, Diane. This is the third book that John and I have written together. Our previous book was called Lead the Work: Navigating a World Beyond Employment, where we looked at different combinations of human talent beyond this notion of a job. We looked at gig talent, alliances, outsources, internal marketplaces, many different ways that organizations could get the work done by humans, be it with different relationships. HBR asked us to write Reinventing Jobs in large part because John and I were increasingly frustrated by the narrative we were hearing. It was two extreme narratives. One was where the machines were going to take all of our jobs and then the others were the opposite where the machines were not going to take all of our jobs.

They were going to make our lives easier and we would have all of this leisure time, which somehow magically would translate into continued income. We’ve realized over the course of maybe 25 years of research and work, separately and together is that automation doesn’t affect jobs. What it does is that it affects tasks which are the components within a job. It does 1 of 3 things. A highly repetitive rules-based work. You might find automation substituting the work of the human. For other more complex work, which requires human ingenuity, creativity, innovation, and empathy. You might find automation augmenting the work of a human. There is yet more work that is created by the presence of automation. If you look at the spike in demand we’ve had for data scientists. All have come about because you’ve got sensors and AI spitting out much data that we’re able to monetize data and turn it into an asset for companies. That would not have been possible without the presence of automation and artificial intelligence. In our book, we have about 130 case studies that illustrate how by getting beyond the job, you can identify what gets substituted, where it gets augmented, and then what new human work is created?

Reinventing Jobs: There are basically two extreme narratives. One is where the machines are going to take all of our jobs; the others is the opposite.

That’s fascinating because it ties into my work with perception and curiosity both when you talk about human talent and some of the things you’re mentioning. It brings up some of what I’ve researched. I think that we need to ask some of these questions to recognize how, where, when can we use this automation? Are companies asking enough questions? What curiosity levels did you see in your case studies?

You see the full gamut of it. You saw companies using automation to completely challenge and reinvent themselves. One of the case studies we have the privilege of sharing and they’ve got a couple of HBR cases written about them is Haier in China. Haier is probably the largest appliance manufacturer in the world. It started off as a regional provincial company in a second-tier city in China. It acquired a number of businesses around the world, including GE’s appliance business. They completely remade itself from a traditional assembly line company where the distance between an employee and the customer couldn’t be greater to essentially 220 micro businesses. Predicated on closing the separation between an employee and a customer to one degree of separation. They have totally embraced automation and AI as being the linchpins for their new business model, such that the role of the corporate center now is not to govern hierarchy and not to decide strategy.

Essentially, it’s to ensure that the right amount of money and the right talent is getting to each of these micro-businesses. One specific example, they own the market in refrigerators around the world and have pioneered a concept called Food as a Service. You may not know that you’re running out of milk in two days, but your refrigerator knows. Your refrigerator knows to place the order with Amazon or wherever it might be and you’ll get a text message saying, “Diane, a gallon of milk is going to show up at your doorstep tomorrow, in time for the one that’s in your fridge to run out.” All of these were ideas that their staff came up with by making the refrigerator essentially a portal loaded with intelligence and sensors.

That to me was a great example of reinvention, but then there are many other organizations who unfortunately lead with the latest, brightest, shiny object. Companies who lead with technology and invariably ended up with a lot of breakage in their organizations. It’s one of the reasons John and I started the book with a quote that has been captured and it’s been repeated many times. The quote is this, which used to be a primary source is, “Once the bedrock of competitive advantage, legacy, whether mindset or infrastructure, is increasingly the primary obstacle to sustainable automation and the future of work.”

The refrigerator reminds me of The 6th Day with Arnold Schwarzenegger. It is when he’s drinking the milk out of the refrigerator, I don’t know if you’ve seen that movie, but I thought, “That’d be cool to do.” They’re actually doing that. When you’re talking about the companies that lead with tech and that can be a problem, I think that that’s an interesting debate. Are they optimizing what they could be doing with humans? Are they replacing them with machines? What do you mean by leading with tech?

What I mean by that is instead of leading with the work, analyzing the work, understanding the role of automation, understanding specifically what it will do versus the human being and how we can get to outcomes that are orders of magnitude better than what we have. We see lots of organizations getting enamored with a piece of technology and then looking primarily at the substitution of humans in the process. Unfortunately, we’ve seen a lot of that through the course of this pandemic. One said to me, “The machine doesn’t get sick,” which is an unfortunate comment but it reflects the reality of thinking. We’ve seen a lot of movement towards what I call dark warehouses and dark factories. Essentially factories that are either autonomous or that operate remotely.

There’s been a lot of that movement over the course of this pandemic. When you lead with the technology, what you often end up with is primarily a substitution play. Often you miss the big opportunities to make a step-change in the process because you’re looking at substituting the work that’s being done by the human. As opposed to saying, “How do I get to the types of outcomes that are exponentially different?” One of the examples we had in our book was a UK based company. It’s a large retailer and they have a sophisticated call center. They started using Emotion AI in the call center. Within about 8 to 10 seconds of a call coming in, the algorithm will classify the emotion of the caller based on the nature of the emotion and its severity.

If your call happens to fall into the bright red, upper right-hand quadrant of that 2×2 matrix, your call is sped through the nine other prompts to that best customer care person. This is someone who has been hired because he or she has high degrees of emotional intelligence. They can communicate with empathy. They can put their emotions aside when they’re dealing with an irate customer or a distraught customer. The algorithm directs the call to that person, but it doesn’t stop there. It’s based on its analysis and prompt that person with a script and a series of words to use and words not to use. To me, that’s a great example of taking a step back, starting with the work, as opposed to saying, “We could spin up a bunch of chatbots to deal with our customers and we could eliminate all of those people in the call centers.”

[bctt tweet=”More work is created by the presence of automation.” username=””]They’ve certainly used chatbots for highly transactional things. The things that people can often get done on a website, but people prefer to call. It used to be that the loss ratio of customers, when they first started doing this analysis, when they started with the algorithm, they estimated that they were losing about 70% of the customers who were in that top right-hand quadrant of emotion both in terms of nature and severity. The cost of using this algorithm and training it, developing it, and hiring people who fit that specific profile of dealing with difficult customers they’ve gotten it down to 13%. It was a great example of starting with the work, looking for a series of outcomes that were exponentially greater than the ones they might have been calibrated to with that previous manual process.

As you’re saying that, I’m thinking as a customer. Do we get further along if we yell, scream, and freak out? If companies do this, do we get to bypass all the things, or is this one company doing this?

I know for a fact that there’s at least this one organization doing it. I would be surprised if there are others with Emotion AI. We’ve seen a lot more of different variants of this. Not quite as sophisticated as this particular one, but different variants of emotion AI come whether its employee-facing tools or customer-facing tools.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation on emotional intelligence. I’m always fascinated with what they can do and what these pieces of technologies you put them on what makes people drawn to them. I think of my Echo that seems to ignore me and listen to my husband. I have to have him constantly talk to her. As companies, we want these kinds of techs that can help us. You’re giving some great case studies of how it’s reducing errors, problems, and helping. How do you stay on top of these trends because there’s much technology? Is that overwhelming to most people?

It is. You almost need a new department or new function in your organization dedicated to staying on top of this. Many functions, I know a lot of clients who have HR functions where they have a role that is the HR lead technologists. He or she is meant to be scanning the marketplace for new technologies, experimenting, and testing them. I know of finance functions that have similar roles. It is and you’re right. It is a ton of work and it requires some real dedication and focus on the part of companies to stay on top of this.

Part of this you’re talking about or writing about as well and reinventing jobs, you say there’s a four-step approach to applying automation at work. Those are you can construct, optimize, automate, and reconfigure. I want you to talk about those in more detail so we can get an idea of what we need to be doing.

Let me take you through each of the four steps and then I’ll use an example and illustrate it in action. The framework starts with the work. Two of the four steps start with firstly taking a job or a process and deconstructing it and asking the question against three continuance. Is the work repetitive versus variable? Stuff that is repetitive and rules-based. Many people operate on autopilot when they’re doing some of those tasks. An extreme example of variability would be the work of an artist. Creating something for the first time, every time. You’ve got work that is performed independently versus interactively with customers or colleagues. The last category is work that is physical versus mental in nature.

Reinventing Jobs: A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work

Against those three categories or classifications of tasks, the second step to then ask the question of, “What are we trying to solve for with each of these activities or tasks?” John was the pioneer of this and we’ve adapted it in our work together, we’ve identified four specific outcomes associated with work. One is where you’re looking to eliminate errors. Think of the work of an airline pilot, or a drill on an oil rig. Much of that work is about ensuring that 100% of people or machines doing the work are operating at least at the minimum acceptable standard. We don’t need a lot of creativity or innovation when it comes time to land a plane. We’ve been doing it the same way since the Wright brothers.

You need 100% of those airline pilots doing it the same way every single time. Eliminating errors is that objective function. You then have another objective function around minimizing variance. Where there’s no return to the company for the work being done faster or better beyond a certain level of performance. You see that in a lot of process work in transaction processing. You have the third relationship, which is one where more performance is better. Think of the work of a salesperson. You have almost a unit relationship between performance and value to the company. There is a fourth relationship which often goes unexplored. That’s why you have an exponential relationship.

That’s where we see work that is highly creative. Data science falls into that. To pick a topic as an example, the team at Johnson & Johnson or Oxford University working on the vaccine. Small increment performance, they’re massive outcome, massive gain to both society and that company. Against these four relationships, you ask the question of what is the relevant type of automation? For work that is mental, repetitive, and where you’re trying to minimize variance. Something like robotic process automation would be relevant to that. For work where you’re looking for an exponential breakthrough, the work is highly variable, it’s cognitive or mental, and it’s performed maybe interactively in innovation teams.

AI might be a useful solution there to provide insight and knowledge much like my call center representative at that region. That analysis of work in the first two steps, step three is to find the relevant type of automation and there were three broad categories we looked at. Robotic Process Automation, Artificial Intelligence, and what we call Social Robotics. Think of it as not your father or my father’s robots from the old Ford or General Motors assembly line. In the old days, equipment was homogenous, did one thing, didn’t move and it was good at highly repetitive things. Now, what you have is equipment that is mobile with sensors and intelligence to be able to process the information or data from those sensors and then interact and work collaboratively with humans.

Amazon’s Kiva robots probably is a great example. Instead of products flowing to the machine like you would in an assembly line. You’ve now got robots swarming to the product and working alongside humans. The fourth step is the combination of the first three and it is a roadmap to tell you, “Where does a particular type of automation substitute? Where does it augment? Where does it transform the work of the human being?” One specific example might be, let’s say, I’m a credit analyst at a bank and you apply for a mortgage. You submit your mortgage application.

My first task is to verify that data, validate that data against the bank’s records, verify that date against TransUnion, Experian, and Equifax’s data. Connect that data to IRS data to verify your income. Maybe do a social media scan on you to ensure that you’re not going to use the funds by any nefarious purpose. All of that work which is highly repetitive performed independently and mental in nature and where the objective function is to typically reduce variance or to minimize errors. Robotic Process Automation could substitute that particular body of activity, instead of me doing it. It could do it much faster. Let’s say interest rates went down and there was a spike in mortgage applications, I could spin up a bunch of more RPA bonds to take on that surge in volume at virtually zero incremental cost versus having to go out and hire a bunch more credit analysts or mortgage application processors.

It’s interesting because I was a loan officer in the past. I could see that being a possibility because I think that there’s much repetitive work there. I think people who are reading sometimes are going, “I’m a loan officer still, where do I fit into this equation when they start replacing us?” How do you deal with that when people ask you?

It’s about having the machine do the repetitive work and then preserving the human to take on more of the stuff that is the decision-making, critical thinking, analysis, and stress testing. Instead of someone plowing through application after application, validating that the information is right. Connecting the outcome from a decision back to the bank manager. I think there’s lots of other more human work that you could preserve with the workforce because they know. One of the big advantages for people who have done the work that’s being substituted by automation is you don’t have the black box problem. You’ve got people who know exactly what’s going into that and now what you want is for those people to do a couple of things, to keep ensuring that the algorithm or the bot is being trained up and it is accurate to keep validating the outcomes. The cost of a mistake in terms of incorrect credit decision could be significant.

[bctt tweet=”Scanning the marketplace for new technologies, experimenting, and testing them is a ton of work and requires real dedication and focus.” username=””]In terms of potentially even fines from regulators, the potential for lawsuits, etc. Also having the people who were previously doing the work and training them to be able to connect those decisions to potentially a bunch of other decisions that might get made. How does this application and the insight gleaned about the customer through that process translate into potentially other products that they might be candidates for? We’ve learned a lot about the customer through this process. Can we start to think more holistically about the entirety of the relationship with them?

What you’re working on is important and I could see why you speak to many important events. I mentioned you speak at the World Economic Forum, but you’re also talking at Oxford, Northwestern, USC. I’ve seen the list of all the people who’ve had you come to speak. You have such an important message because I think many people are frustrated. They’re worried and they don’t know what to expect. Your work spells it out clearly. I loved how you went through those four steps because then people can get much from that. I think they’re going to want to read your book and find out more. I was hoping you wouldn’t mind sharing a website or somehow, they could follow you.

I’m on LinkedIn and Twitter Ravin Jesuthasan. That’s also the website as well as the WillisTowersWatson.com website, where we have a lot of great collateral around the work that I’ve been doing.

I know you do some amazing things and congratulations again for getting nominated. I look forward to get to meet you in person at the event in London. Thank you much for being on the show.

Thank you, Diane.

Technological Business Transitions With Jed Ayres

I am here with Jed Ayres, who is the Global CEO at IGEL which is widely recognized for the transformational impact they make on end-user computing industries. He plays a role with tech companies helping them transition into cloud computing. I know we’re doing a lot of that with COVID. It’s nice to have you here, Jed.

Reinventing Jobs: When you lead with the technology, what you often end up with is primarily a substitution play, and very often, you miss the big opportunities to make a step change in the process.

Diane, thank you so much for having me.

Where are you in California?

I am in Marin County. I’m across the Golden Gate Bridge at a base of Mount Tam, a little city nobody has probably ever heard of, but it’s called Kentfield. It’s where mountain biking started.

That’s not Sausalito’s direction the other way.

That is a little bit past Sausalito. There’s a big mountain which is the tallest mountain. It’s a neat little spot.

My daughter lives in Sunnyvale, I get up there quite a bit because her husband works at Apple. Plus, I’m beyond the board at DocuSign and different things that I do. I get up to San Francisco quite a bit. I’m going to have to check that out.

We love this company. We started using it inside of our job, a little late to the game.

I know Keith Krach well who wrote for my book. He was the Chairman-CEO of DocuSign before he went to be in government. I think that there’s a lot of great software. You’re definitely where you need to be around these successful tech companies up there. I want to get a background on you to know a little bit about what led you to become this Global CEO.

[bctt tweet=”Every human is wired a little differently in terms of their capacity to work entirely remotely.” username=””]I was born in Northern California in a little town of Mendocino. Four hours north of the Golden Gate Bridge. I guess I got the lucky lottery card to be born into the hotbed of technology. I’ve spent 25 years in tech and selling tech. Being in and around all of this innovation that’s come out of Silicon Valley. I started with this company IGEL years ago, which on the surface, a lot of people looked at it. Mentors of mine looked at it and said, “This does not look like a great career move.” They couldn’t see what I saw when I met the founder, who was a German guy who had been working on building this company up for many years.

It was a European German centric company that was building thin clients. You have another name for thin clients is dumb terminals. A German company that was building hardware, that was in a space called Virtual Desktop Infrastructure, which was a small use case. Not a lot of people, unless you were in banking, finance, healthcare would have ever even used it. A lot of people told me, “Don’t take this job. It doesn’t look great on the surface.” What I saw was something that a lot of people miss when they looked at the company, partly because it was all done in German, and German don’t tend to be great marketers. They’re more engineers. The marketing was technical, but underneath the hood was this operating system that was built on Linux. I don’t know how technical your audience is but everywhere you go in the world where you’re on a stable, secure operating system, whether it’s in a Tesla, an ATM, or even in the cloud. A lot of the operating systems that are hardened, secure, and high are built on Linux.

That’s interesting because I’ve had Richard Stallman on the show.

He is the man. That was what I saw. These guys have this twenty-year history of building an operating system that can sit under these cloud-delivered services, namely, the ones coming from Citrix, VMware, Microsoft, and Amazon, the four leaders in this space. What we see is a massive pivot. It’s going to be accelerated by COVID, which is this idea that everything’s going to get delivered out of the cloud, including all your Windows applications and Windows desktops. The Bill Gates era of, “I’m going to put a desktop on everyone’s desk. That desktop is going to have an operating system and locally installed applications. Every three years, you’re going to throw that machine away and you’re going to put an even bigger more complicated operating system and a bigger processor on your desk.” We believe that you’re coming to a screeching halt. You’re going to have a different architecture. It’s going to be a light, secure, high performance, specially tuned to connect to these cloud services operating system on a much cheaper device. Some equality entering into the equation like the Chrome brick architecture but in a much bigger ecosystem of applications to attach it to. Specifically, Windows applications.

I think that a lot of people who read the blog are tech-savvy, but then there are some where they hear terms and they’d like to know more. Can you dumb it down for some of us? For the edge computing, for example, is talked about quite a bit. Being on the edge, not as part of the cloud and what’s the cloud, what’s the edge? People know cloud computing, they have the basics on that, but this edge thing is confusing to some people. Can you give us a little bit more about that?

The edge is where you’re going to interface with these technologies that are going to come from the cloud. Go to an electronics store, almost anything that you’re going to put in your house has become connected. If you’re putting in new thermostats or this whole idea of smart connected everything, speaker, thermostat, refrigerators, and alarm systems all being connected. The world that we see comment coming into focus is this hyper-connected edge where there’s a lot of analytics and data that can come out of all these connected devices. A lot of efficiencies in terms of how things are used.

It’s a beautiful thing when it’s working correctly. I think in the world that we live in, it’s more about the world where you have a human being sitting behind a device that’s doing some work, whether that’s a repetitive task or full knowledge work or the most sophisticated community computing tasks that you could imagine on CAD. People that are doing the next Pixar movie. The theory is that you want to be able to deliver it to them from the cloud a high performance, highly secure, manageable experience to a device. It’s any device. You want to be able to move from your iPhone, iPad, desktop, and you want to be able to do it anywhere, unlocked and unleashed from a specific location.

Reinventing Jobs: Everywhere we go in the world today, we expect to have technology that is stable and secure.

You want to be able to do that computing securely, and you want it to be super high fidelity. That’s the promise. I think you’re going to see the acceleration and innovation around this coming out of COVID. If you think about the number of people that were able to work from home, it might’ve been 10% of the population. In Europe where we have a lot of our employees was even less. Six out of ten people had never worked at home. What COVID did was all of a sudden everyone needed to work at home around the world. We went from maybe 100 million people working from home to hundreds of millions of people working from home. It broke the barriers around conventional thinking about which jobs could even be done at home. We have some remarkable stories around that where lower-level entry-level, back-office level jobs, entire call centers that would have been in a building where people were commuting to every day.

Thousands of people working the phones suddenly, they’re all working at home. The remarkable thing is that what we’re seeing is the productivity, the customer stat, the efficiency, and many of these cases gone up. It shattered a lot of somewhat antique thinking that was out there that these jobs can’t be done unless I can see these people. As we climbed back into a new normal, what I would expect is that you’re going to see new thinking that’s going to creep in in terms of how office work is structured. I don’t think you’ll ever see the days where thousands of people all go back into massive buildings. It’s not as good for the planet. It’s not as good for the people. I think this COVID showed it’s not as good for the organization. It’s an exciting time.

I’ve always worked virtually. Almost every job in the last decades has been virtual. When I did go back working in an office, it was hard for me to stay motivated. When I work at home, you can’t keep me from working. When I’m in an office, for some reason, it’s much harder for me to keep as focused. I teach a lot. I’ve taught more than a thousand online business courses and a lot of the students have a hard time keeping up with being motivated. They’re not like me. I think some people have a hard time not doing their laundry or whatever it is they do when they’re at home. How do you keep the morale high and keep people motivated? Are you running into a lot of issues with that?

I think every human is wired a little bit differently in terms of their capacity to work entirely remotely. I also think there are few people in the world, the human condition is one where we’re wired to collaborate and connect. I hope this isn’t forever. As good as Zoom might be, or Teams, Webex, you still don’t get the energy that’s exchanged and some of those things that happen in the casual office setting. It’s hard to recreate that. We’re trying and this is where I think some of the innovation will come. Also, you’re going to see hybrid models that come out of this where people still meet face to face, but it’s even more special. It’s reserved for special moments where you need that face to face energy to break bread or collaborate in a conference room.

That is one of the biggest issues I face as the CEO. I’m a new CEO globally for this company. I took over February 6th. You could imagine, 2/3s of my employee base is in Europe. I stood on a stage in front of all of them. I took the torch. We had lit torch on the stage from our founder that had been working on this company for 30 years. I said, “I’ll be back shortly to connect and calibrate with 2/3s of our employee base.” Later, I got locked down in my office and I couldn’t even fly to Germany if I wanted to. This has been a remarkably interesting start to this position. Luckily, I had a three-year history in different roles as the CEO of the US. I was already connected with a big portion of the population. It’s been a challenge to try to meet people where they are, in their houses.

My advice to any leader out there is transparency, authenticity, flexibility, agility, these are all the new superpowers. Listening to your employees. I like to have a digital relationship with my employees. I must have hundreds of people’s cell phone numbers in my phone. My open-door policy is my texting. It aggravates some of my team at times because people will go through chains of command to text directly to me. To me, that’s how you keep a pulse on. How can you keep track of what’s going on around the world? If you have an open-door policy in this era, that means you need to be able to have people email you or text you and feel that it’s okay to do.

I had Zander Lurie on, and he does a lot of skip-level things at SurveyMonkey because their whole culture is about developing curiosity. They even changed the address where they work to like one curiosity way or something similar to that. They have the importance of asking questions and having people have that sense that they can give insights and don’t have to worry about being cut off if they do have a question or have that ability to ask a couple of levels up. I worked in a company where all the leaders sat on the top floor. You didn’t have a key to get up there. You couldn’t get out of the elevator and get into the room without a key. They never came down and you could never talk to anybody.

The best mentor I ever had in my career was someone that pointed to me about shoe leather management. This was back when I first started my career in San Francisco and we had an office with maybe 150 people in it. I remember he had the corner office like you would expect. That was the biggest fanciest office with the secretary sitting in front of it, guarding it. What he did that was different than a lot of people like you suggested was that at least three times a day, he would walk around the office and he would say, “What’s happening? Tell me something good that happened? Tell me something bad that happened? What challenges are you facing?” He learned more and not walk through the office three times a day than he did sit in meetings with VPs all day. I took that to heart. How do you recreate that in the COVID era? It’s about curiosity.

[bctt tweet=”The human condition is designed to collaborate and connect.” username=””]I was on a podcast with a guy and he asked me, “What’s changed in the selling process for you in COVID?” I thought, “I think the processes in terms of how people are buying things have changed. The people in some cases and our customer are being changed around. There are layoffs.” The priorities are changing. I said, “That’s my view of it.” I need to go and ask the people. I’m texting fifteen different people across the section of my company. I’m getting real-time results. I did an all-hands with our European staff. We were talking about the uncertainty. I took three of the responses and I put them in all-hands. I said, “These are three people that you all respect and trust. This is what they’re telling me.”

It’s a different way to communicate sometimes with texting than what people are used to. As you’re saying that, it reminded me when I was in education and one of my jobs that we had Skype, it was on all the time where I can’t remember what version of Skype it was. I had a good boss at that time who would every once in a while, you’d see something like “Good Morning.” He’d say something to let you know he’s there. It wasn’t like checking on you to make sure you’re at your desk or something. If you didn’t answer, it wasn’t a big deal, but you always felt like he was there. As you were talking to about this walking around thing, I had interviewed Douglas Conant a couple of times who was the one who turned Campbell Soup around and he’s in every case study and other course I’ve ever taught probably. He was able to do to create great engagement by writing notes to each individual person in the company. He said he wrote over 30,000 notes to people handwritten throughout the whole time he was there. I think that there are a lot of ways we connect. Trying to do that virtually is going to be a challenge. It’s tough as a leader. What do you think is other than texting? Are there other ways that you’ve found you’ve been able to connect?

We’re doing all the things that you would expect in terms of hosting, all hands, and being prescriptive about that. Opening up a Q&A and making it transparent that you can ask us anything. I’m following the John Chambers playbook of here’s a guy who navigated five different crises and dominated many different categories and came out of some of these crises as the leader in them. His whole story is to be authentic and be clear with what your playbook is. That’s the playbook I’m using which is to be authentic, be clear, and regularly update people. We’re having lots of town halls. One thing I would say to all leadership teams is you can’t do this by yourself. We’ve solidified our extended leadership team. We have 35 people in the company, some higher-level titles, and are managing smaller teams. We spend a lot of time with that team. Getting the feedback from them, what are the challenges, or how is it going? This is what we’re thinking about as far as our strategy and then navigate through this crisis and that’s been helpful. During the height of all the changes with this COVID, we were meeting with them twice a week. It’s backed at once every two weeks, but being intentional about those touchpoints and trying to take it to the actual individual contributor or as much as you can and keep it flat. You can learn a lot by opening your ear.

You talk about not doing it by yourself, and I’m sure you have a board and different people. I’ve talked to a lot of companies. I’m curious since California had their law of having women on boards a certain number, how has that impacted your board? Do you have cultural experts and people like that to be proactive for this type of thing of how to rearrange and how you work in times of crisis?

Another interesting thing being a German-headquartered company is that some of the progressive things that we think about as a Silicon Valley tech company aren’t totally in sync in terms of how boards are set off and the whole hierarchy of GmbH. This has been part of the magical IGEL story. As we’ve made this journey over the years, we’ve doubled the size of the company for the first time in the 215-year-old history of our parent company. That’s the major shareholder company called Melchers. They’ve got success on their hands in the United States. This has never happened even though it’s a billion-year-old company with 50 different companies. They’d never had penetrated the US in any form, let alone with a tech company.

It’s a remarkable story. It’s been interesting to see the marriage of some of the US cultural attitudes around diversity. How boards are shaped, the powers of boards, and the governance of companies. I was proud as we hired the first 100 people in the United States, 40 of them were female. I can tell you, and I’m sure your audience knows this that that’s not a standard ratio in the tech world. Especially not in the dark arts of end-user computing, cloud computing, Linux. These tend to be an extraordinarily male-dominated industry. We sought out that and part of the success that we had in the last years is born out of diversity. Don’t hire people that look like yourself. Hire people that are highly qualified, seek diversity and that empower them. That’s been my formula.

I’m hearing a lot more of that. I know California is ahead of other states in being proactive for the women on boards and different things. It’s always interesting to hear what’s working and what’s not working for companies. I think some companies are still having a tough time working remotely and getting everything connected to the cloud the way that maybe they didn’t before. How are you helping them in this time?

Reinventing Jobs: People should have a relationship with each other that is built on transparency, authenticity, and flexibility.

We see it in three phases. There was a rush out the door when people realized that by law we have to shelter in place. A lot of companies weren’t prepared for that. It was like a fire drill. You grab your belongings and get out the door. All of a sudden, they found themselves at home with where they thought maybe a few days away, this is going to be a week, this is going to be for way longer than that. People were scrambling to buy equipment and to figure out how they were going to do this, which has been neat for us because the people that we work with and these organizations suddenly we’re on the phone with CEOs and boards on a daily hourly basis trying to figure out how to make up for the lost time.

Things that they’d never architected before. I think that we find ourselves in the midst of phase two of this, which is like if you’re a hospital and you had hundreds of people that went to that hospital every day to perform back-office invoicing functioning. That’s the lifeblood of a hospital. They’ve got to get paid. Those people had never worked from home before. How do you deliver a super secure, high fidelity connection for them that allows them to meet all the regulatory requirements around how they touch data? What IGEL is working on is the longer-term strategy. I think everyone in every company is figuring out their business continuity strategy and business continuity probably meant something else. It was like, “If there’s an earthquake or this office gets put offline, or this data center gets put offline, what’s our backup plan for that?”

Now business continuity is like, what happens if everyone has to work remotely again? That was never something a lot of companies haven’t thought about. That’s where we’re helping companies. The best and most efficient way to do that is to get all of your applications and data out of the cloud and be able to have all that stuff deliver to any device anywhere. That’s what we’re helping people with. I think then there’s phase three, which is going to be the new normal. That’s probably where you’re also going to see this hybrid between office locations. You’re going to see a much scaled-down version of offices going forward. It’s too attractive. You’re an MBA professor. You know this. When you look at the cost of the company, it’s the human cost. Right below that is your real estate costs typically. This enticing reality of we’re just as productive if not more productive and we can take this huge cost out. Recalibrate some of that investment that was hardened into buildings, back into humans, innovation, and other constructive things. I think offices are still going to be important. They’re going to be a slightly reimagined office.

It’s going to be interesting to see what comes of all of this and all the changes. I’m all for virtual work because I love to work that way. You do some amazing things at IGEL and I think a lot of people are going to be interested in finding out more about what you do and be able to follow you somehow. Is there some link or some way to follow you that you’d like to share?

I would love to connect with people. I’m a firm believer in your network is your net worth. I’d love to carry on the conversation over LinkedIn. It’s my preferred way. You can find me there Jed Ayres. If you’re interested in more about the technology, IGEL, and what we’re doing, we’re disrupting, dominating, and haunting this new category of an edge operating system that will be connected to these cloud workspaces. You can go to IGEL.com. You can download the operating system. You can connect to these services and start to play with it. We’d love to talk with you more about how the world’s changing and how we can help you. The hamster wheel of an ever larger, more complicated, operating system that’s in an ever more expensive complicated powerful process around the edge. We think those days are over. It’s marked by Apple. They said, “Arm on the edge.” That’s a low power consumption processor. We think that’s where the world is going. The edge is changing. It’s getting bigger and it’s going to be an important part of this new architecture between the cloud and the edge. We think Linux will win as it’s one in all these other areas.

This has been interesting. I hope people reach out to you. Thank you much for being on the show.

It’s my pleasure. I hope everybody stays healthy and safe out there. Wear masks, and do all the right things. Be kind to each other more than anything else though.

—

I’d like to thank Ravin and Jed for being my guests. We get many great guests on the show. If you’ve missed any past episodes, please go to DrDianeHamilton.com. You could find out more about Cracking the Curiosity Code and the Curiosity Code Index as well as the Perception Power Index, and much more on the site. I hope you enjoyed this episode. I hope you join us for the next episode.

Important Links:

- Ravin Jesuthasan

- IGEL

- World Economic Forum

- Willis Towers Watson

- Reinventing Jobs: A 4-Step Approach for Applying Automation to Work

- Lead the Work: Navigating a World Beyond Employment

- LinkedIn – Ravin Jesuthasan

- Ravin Jesuthasan – Twitter

- Richard Stallman – Previous episode

- Zander Lurie – Previous episode

- Douglas Conant – Previous episode

- Melchers

- Jed Ayres – LinkedIn

- Cracking the Curiosity Code

- Curiosity Code Index

- Perception Power Index

About Ravin Jasuthasan

Ravin Jesuthasan is a recognized global thought leader, futurist and author on the future of work and human capital. He has led multiple research efforts on the global workforce, the emerging digital economy, the rise of artificial intelligence and the transformation of work. Ravin has lead numerous research projects for the World Economic Forum including its ground-breaking studies; Shaping the Future Implications of Digital Media for Society, Creating a Shared Vision for Talent in the 4th Industrial Revolution and HR 4.0: Shaping People Strategies in the 4th Industrial Revolution. He is a regular participant and presenter at the World Economic Forum’s annual meetings in Davos and Dalian/Tianjin and is a member of the forum’s Steering Committee on Work and Employment.

Ravin Jesuthasan is a recognized global thought leader, futurist and author on the future of work and human capital. He has led multiple research efforts on the global workforce, the emerging digital economy, the rise of artificial intelligence and the transformation of work. Ravin has lead numerous research projects for the World Economic Forum including its ground-breaking studies; Shaping the Future Implications of Digital Media for Society, Creating a Shared Vision for Talent in the 4th Industrial Revolution and HR 4.0: Shaping People Strategies in the 4th Industrial Revolution. He is a regular participant and presenter at the World Economic Forum’s annual meetings in Davos and Dalian/Tianjin and is a member of the forum’s Steering Committee on Work and Employment.

About Jed Ayres

Jed Ayres, IGEL’s Global CEO, is widely recognized for the transformational impact he is making on the end user computing industry, as well as the instrumental role he has played in IGEL’s pivot starting in 2016 from a hardware-centric to a software-first company. As Global CEO, Ayres leads IGEL’s seasoned team of executive leaders as the company works to align with the world’s most prominent cloud providers to transform end user computing by simplifying and securing the cloud-delivery of all needed applications and resources.

Jed Ayres, IGEL’s Global CEO, is widely recognized for the transformational impact he is making on the end user computing industry, as well as the instrumental role he has played in IGEL’s pivot starting in 2016 from a hardware-centric to a software-first company. As Global CEO, Ayres leads IGEL’s seasoned team of executive leaders as the company works to align with the world’s most prominent cloud providers to transform end user computing by simplifying and securing the cloud-delivery of all needed applications and resources.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

0 Comments