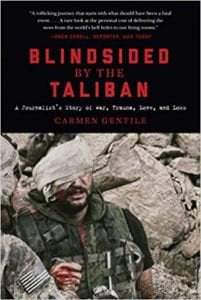

I’m so glad you joined us because we have Carmen Gentile on the show. He is a veteran journalist and he was shot by a rocket-propelled grenade. He has an amazing story. He’s the author of Blindsided by the Taliban and he is going to tell us that story.

Listen to the podcast here

Blindsided By The Taliban: A Story of War, Trauma, Love, and Loss with Carmen Gentile

I am here with Carmen Gentile, who is a veteran journalist who has covered the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and numerous bouts of unrest throughout the world, from Haiti to El Salvador. He was seriously injured while reporting in Afghanistan on an experience he chronicles in his book, Blindsided by the Taliban. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, TIME, Esquire, USA Today and a lot of other publications. He’s very interesting. I’m so happy to have you here. Welcome, Carmen.

Thanks for having me. I appreciate it.

You’re welcome. You’ve got quite a story. It was a horrifying thing that happened to you. When I watched the video, it’s hard to believe what you were watching at the time. I want to set the stage for what we’re going to talk about in terms of what happened to you by giving a little background of you as a journalist, what you were doing, and why you were in Afghanistan and all that. Can you lead up to that point?

This was back on September 9, 2010. I was embedded with the US Forces in Eastern Afghanistan a couple of miles from the Pakistani border. We were walking through a small village deep in the mountains and it was around sunset, the last day of Ramadan. We were talking to some young men on the side of the road and I heard a whooshing noise. I turned around and saw a man about 40 yards down the road, cradling a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. From the end of that launcher was a beeline of smoke and at the end of that beeline was a conical tip of an ordnance coming right at me. The grenade hit me in the side of the face without detonating. It blinded me in the right eye and fractured the right side of my face. Fortunately, for me, it did not go off or we wouldn’t be having this conversation, rather, it blinded me and seriously injured me and then clattered to the ground.

I could feel my hair on my arms go up as I listen to this because I have watched this video and what that must feel like to see that coming at you. It was disturbing to watch because you were video recording this, so you get to see the camera fall to the ground. You could hear that you were hit and you handled it very well, by the way. You were very calm considering what happened to you. I’m wondering now were you behind the camera taking it or were you the one asking the questions? What was behind what we can’t see?

I was holding the camera and I was interviewing some people on the side of the road, asking them a couple of questions about the Taliban. I already had a hinky vibe about what was going on there. We weren’t very well received there. A lot of folks weren’t that happy to see us there. Having done this work for quite a long time, I knew something was wrong. As you mentioned, the hair standing up on your arms and on your neck, that was the exact same feeling I had moments before. I knew something was going to happen and I didn’t realize it was going to be that severe. When I was hit, it didn’t quite resonate with me that I had lived.

My right eye had gone black immediately and I thought, “This is it. I just died. This is the end of it and this is what dying is like.” I hit the ground and thought it’s over. I realized a few moments later that I had not died, rather I was very seriously injured and that’s when the blood started pouring out of me. The able hands of the medics and other soldiers around me were treating me immediately while at the same time defending against a would-be second attack because that’s how the Taliban likes to operate in those types of situations. They’d rather injure one person in an initial attack. Then when they’re treating the injured, that’s when they come in with the second attack and wipe everyone out. That was what was frightening at that moment, everyone else is getting killed too.

[bctt tweet=”The difficulty of the fight is that you don’t know who is a friend and who’s a foe.” username=””]Were those three men on the ground have anything to do with it? Did they know that was happening or were they innocent?

The difficulty of the fight is that in Afghanistan, you don’t know who is a friend and who’s a foe. Do I think that they had anything to do with it? I don’t know and I don’t think so, but it may very well have. Often, you’ll see even young boys outside of the combat outposts and other young men with cell phones know that when the vehicles are leaving to go on a mission. It was where when soldiers were on foot on a mission, they were making phone calls to the Taliban elsewhere, hiding in the mountains to let them know that the military is coming. You can’t tell. Somebody who seems friendly and is chatting with you could be someone who’s an informant for the Taliban. That’s what makes it so difficult. It was one of the many reasons. It was so difficult for those guys.

Do you know why it didn’t go off? Is there any reason?

No, the common perception is that the guy who fired it was too close. Those weapons are designed to commit a certain number of rotations to arm themselves so that in the case where they do fire it from very close range, the person who’s firing it isn’t also injured in the blast. He may have been so close to me that it hadn’t gone far enough to go off. That may have been the reason or maybe it was a dud. I’d say 40 yards, but it may have been closer than that because I can see the whites in the guy’s eyes. He was staring right at me and I thought, “This is it.” I saw the thing coming at me and it was a fraction of a second that felt like a year, but I was glued to the ground. I couldn’t move. I watched this thing come right at me and it clobbered me on the side of the head. It was like being whacked across the face with a lead baseball bat. That’s what it felt like.

You were looking ahead at the young men on the ground, but then you turned around. I’m trying to figure out.

When I heard that sound, I saw their faces ashen. I heard the sound and I turned around. I had to do a quarter turn to my right and there it came. This ordnance was screaming right at me and I was frozen in panic. I went from complete and utter fear of resignation that I was going to die in a fraction of a second. I can remember that sensation of almost a Zen-like calm at the very end of it thinking, “This is it. The lights are going to go out.” When I got hit in the side of the head and my eye went black, I said, “I died.” I only realized I hit the ground that they hadn’t killed me. I couldn’t fully comprehend what exactly had happened.

It went so fast. Did the boys take off at that point or did they stay there and try to help?

The US soldiers didn’t return fire. Unfortunately, for us, that was the lone attack. There was no follow-up attack after that.

What about the guys you were interviewing? Did they take off?

Everybody took off. This is a small village. It was a single lane dirt road with a couple of stone huts along the side of it and on the other side was a cornfield. There weren’t a lot of folks around, to begin with and when that happened, everybody cleared out. From what I could tell, I was being treated. I was half blind and in a state of fear and shock. I was absolutely shocked, I had lost a lot of blood.

Did you know that there was a potential threat of you getting hit by a missile or whatever in that area?

They were in that same company, from 101st with whom I had been embedded. They had gone out to patrol the night before in that same area. One of their up-armored vehicles called an MRAP, a multi-ton heavy plated armored vehicle that is capable of withstanding IED blasts and all kinds of other ordnance had been hit in the engine block by an RPG and it disabled the truck. They had to tow it back and it was from that exact same area. The threat was there, but I didn’t think that I would get hit in the same way and surely not survive. It was a trillion and one luck that I was not killed. I should have been killed without a doubt.

What makes you want to do that to begin with? Who were you reporting for? Were your parents mortified that you were there in the first place? Can we get a little backstory on that?

I’ve been covering conflicts for quite some time. I first started covering bouts of unrest and other types of conflict in 2004. I covered the coup in Haiti and to this day that’s some of the worst things I’ve seen in terms of the killing, violence and mutilation. It was awful. The following year in 2005, that was when I started covering the war in Afghanistan and later that year in Iraq. Since then I had been going to Iraq and Afghanistan and then covering other bouts of unrest elsewhere in the world for the last thirteen years. At that point in 2010, my folks were pretty used to the fact that I was doing it. I’d spend quite a bit of time there and in Iraq and other places around the world. They weren’t pleased that I was doing it, but they knew that it was something that I did.

What drew you to want to do that?

Every time I’m asked that I give a different answer, so let me cook up something for it. They’re all true, but they’re all different. I have a certain yearning and a melody. It’s a yearning to want to be in places where things are happening that I don’t read, I couldn’t possibly understand unless I was there to witness it. In a sense that I want to do it so that I can better comprehend the more extreme moments in the human condition, let’s say. The melody is something. There’s got to be a screw loose in me because I keep doing it.

I am writing a book on curiosity. Is there a morbid curiosity there?

It’s not so much a morbid curiosity. At this point, it’s a reaffirmation of every bad inkling I have about the human race. It keeps being reconfirmed for me, but it’s not as though I have to continue to verify that so that my disdain or my disappointment with humanity can be reaffirmed. It’s something that I also know how to do. That’s another thing that propelled me to continue to do it. I know how to do it and it’s not something that a lot of people can do. I’m not that good at doing much else.

I doubt that.

We all have our strengths and weaknesses. I took three years of piano and I can’t remember much of it.

I’m curious how has this changed you now though? Do you still do this?

I was in Iraq working on the follow-up to what has been going on in Mosul. I covered the fighting in Mosul between the Islamic State and the Iraqi Forces all of 2017. I was in Iraq on and off half a dozen times and that was a bad situation too. It was terrible. That city was destroyed. Many lives were lost and that was some of the worst destruction I’ve ever seen. It’s something that I still do.

[bctt tweet=”It was a trillion and one luck that I was not killed. I should have been killed without a doubt.” username=””]I watched Homeland, I watch stuff and I was thinking of the Diane Sawyer interview that was on Oprah a long time ago where she talked about her accommodations of work and when she would go on these things where she’d have cockroaches in bed with her. I’m so high maintenance listening to this. I can’t even imagine. What are your accommodations like? Are you sleeping out on the ground? How do you deal with that part of when you’re covering these stories?

The combat outposts that are in rural parts of Afghanistan are pretty bare bones of accommodations. The combat outpost where I was placed called Pirtle-King was where I had spent quite a bit of time there. They didn’t have any running water. They were only getting one hot meal a day. These guys hadn’t had their clothes cleaned or themselves showered in about a month. Everything was baby wipes and recycled socks. They’d given up on their underwear months ago. There were grime and caked filth. In retrospect I think, “That’s gross. I hate that. I don’t ever want to do it again,” but then once I’ve made it, the bar for how bad things can be keeps getting higher and higher. It’s not that bad at the moment, but only in retrospect you do think, “That was terrible.”

I’ve seen documentaries like The Heart of Nuba, it was a friend of ours, Ken Carlson who did this documentary and you see how people are living and how certain people give up their lives like this doctor in that movie. It was pretty impressive. What you’re doing is amazing and what you guys are able to tolerate. Many people would not be able to do what you’ve done even if they didn’t get hurt. Now that you’re hurt, you’re shot, you know you can’t see, you’re bleeding, what happened at that point? Where did they take you? What happened after that point?

After that point, I was emergency evacuated. They called in for a helicopter to bring me out of the hot zone there. I was emergency evacuated out to the US military hospital at Bagram Airfield.

In a helicopter?

I was being treated by medics in the helicopter. They brought me and I had an emergency operation right there in Afghanistan. There happened to be an Air Force ophthalmologist on staff who went in and managed to do a temporary repair on my eye. The globe, the eyeball itself had been lacerated. There is a jelly that’s inside your eye that gives it its nice firm shape. All that jelly had come out and spilled into my head cavity. He pulled all my eye out and grabbed all that jelly, then put it back inside my eyeball and stitched the eye up. When I woke up in a narcotic haze after so many hours, I had a bandage on my head. It was covering over my eye and wasn’t quite sure at first what had happened.

Then it started coming back to me and the nurse was telling me that they had the operation and that I would then soon be flown to a US military hospital in Germany. She threw in as an aside almost, “You’re probably going to lose that eye.” Amidst all the painkillers, I thought, “I’ll be fine.” Later, when they took me to the military hospital in Germany along with many other soldiers who had been recently injured, I spoke to a doctor there and he said, “We’ll see, maybe we’ll be able to fix it.” It’s all about that diminished expectations.

The doctors in the civilian world probably do the same thing. They don’t want you to get your hopes up too high, and then promise and over deliver. That’s something I should probably do in my professional life as well. They gradually said, “We might be able to fix this at least partially.” Later, I was flown again to New York City where I had my several surgeries over a few months to repair the eye and put a corrective lens stitched all right onto my eye. It’s like a permanent contact stitched on the eye. I had a major reconstructive surgery on my face to bring it back to shape and form. I have twelve pins and four plates in my face to this day.

My husband is a plastic surgeon so I’m going to make him listen to this. He’ll find it fascinating. My dad was born blind and he only had 2% vision. His retina was completely detached from his right eye, so he didn’t see it all out of his right eye and he saw 2% out of his left. Later in his life, they had to take off the retina and it was a contact they had to put it in to make it look like he had blue eyes still instead of it being all white. When you’re talking about this, it’s reminding me of some of the depth perception issues and the things you have to deal with now. Did they give you any extra pay? Did you get anything out of that financially because of what you went through? Who do you sue? What do you do for that? Is there anything you can do?

I was working for an employer at that time that was a little slow in paying me the workman’s comp that I was owed. It was certainly not what you would consider a large payment and I had to go to court to collect it. That was not a large sum.

There’s no replacing eyesight.

I did have to sue my employer at that time. I was working freelance for them. There was a compensation not only for my eye but for the laceration on my face to this day, so for partial disfiguration, although I’d look fine and for the loss of vision. I still have the eye, but I can’t see very well out of it. Out of this right eye, I can’t read a stop sign.

You do have some vision from it.

I do have some vision but the problem is that the vision is blurry and there’s a wrinkle in the lens, so it’s a little bit wavy as well. It’s sensitive in that it feels as though someone’s always gently blowing right in my eyes. When I’m home alone, I always wear my eye patch because if I’m looking at my computer or reading anything, I have two separate distinct fields of vision and it gives me a headache, so I keep the eye covered. When I’m outside day or night, during the day I wear sunglasses. In addition to it being wrinkled, my pupil is fixed and dilated on my right side. Everything’s bright out of my right eye, so I always wear sunglasses even on a rainy day. At night, I have these hideous, yellow tinted lenses that I wear. I call them my grandma-still-drives-the-night glasses even though she shouldn’t. I wear those and I don’t care just so I can be comfortable.

Can you still drive?

[bctt tweet=”We all have our strengths and weaknesses.” username=””]I can still drive. I don’t like to drive in the dark though. I’m not comfortable driving at night in the dark. The irony being is I still ride my motorcycle. I’m more comfortable riding my motorcycle than I am driving the car because there’s more room for error as to in terms of your perception of, “Am I in the lane? Am I not in the lane?” When you’re lining up, how far am I away from the car in front of me or behind me? I feel more comfortable on my motorcycle making those assessments than I do a four-door vehicle.

This thing that hit you, I’m envisioning, was it a pointy rocket or was it a round grenade?

It’s called an RPG, rocket-propelled grenade. I’m sure you’ve seen them in the movies. It’s the thing you cradle on your shoulders a long tube. The ordnance has a long end with a conical tip. That shoots out of it and you hear that.

It’s like the Wile E. Coyote rocket, right?

Yes. You probably remember in the movie, Black Hawk Down, when they were in the helicopter and the guy falls out of the helicopter. There’s the incident where they’re yelling, “RPG,” and you could see the RPG coming right towards the helicopter. Then the pilot maneuvers out of the way and the guy on the rope loses his grip and falls to the ground.

Did it hit you dead center in your eye or could it have gone into your brain?

It hit me right in the corner at the top of my cheek, right below my right eye and the pressure caused a rippling, cracking, fracturing throughout the right side of my face that reached all the way up to the top of my eye and through my cheekbone. When I looked at the X-rays before my injury was repaired, it looked like a jumbled box of matchsticks in there. Everything had been torn into a shard, scattered in a million pieces. Initially, the doctors were going to shave a piece of bone off the top of my skull and graft that to my face. It meant that they would have to make an incision along the top of my head and then pull my face down, which I’m happy they didn’t. Instead, they opted to go through the laceration in my eye and opened that laceration that goes from the corner of my eye down to my cheek. They pulled the side of my face apart that way and then went about operating on my face. I had two back-to-back surgeries about a week after the accident after my injury and I was under for a total of about seventeen hours.

In the past, my husband has done a lot more of reconstruction than he does now. In facelifts, they pull your face off the bone like that. I don’t know if they still do, but I know that they did. He used to reconstruct jaws. They would take out their entire mouth and rebuild it from mouth cancers. Some of the stuff you’re talking about, they put plates and do all these crazy things. They take flaps of muscle and different things from their arm to make the interior of the mouth and rebuild jaws.

He used to come home and share some of the stuff that they could fix and it’s amazing what these people have to go through, the surgeries. He would be talking about how cool it was that he was able to do this. It’s hard not to think what you were going through on the other end. What kind of posttraumatic stress did you go through and what did you go through afterward?

I took myself to the psychological woodshed for about eight months after that incident and repeatedly relived it. Not only that, because of my injury I thought that I wasn’t entitled to do whatever I want and act any way I wanted to the extent. About four months after I had been hurt, all the goodwill and sympathy that I had earned, everybody has had enough of me. They were tired of dealing with me and it took me a while to wring myself in, so to speak. One of the ways in which I did it was by returning to Afghanistan. I had been on doctor’s orders forbidden from working from September 2010 until May 1st, 2011 and two weeks into May 2011, I was back in Afghanistan.

How old were you when this happened?

When I first started, I was 36.

Your story reminds me, I had Tanner Gers on my show. He is in Arizona where I’m from. He had a car accident. He became blind in one eye when a tree branch went through his car and went through his eye. It impaled his face. He went through something very similar. He ended up becoming a Paralympian winner and all kinds of things he did later. I’ve had Erik Weihenmayer and a few other people who have lost their sight and had horrible things happen to them on the show. I remember Tanner was saying that he felt sorry for himself for a long time and you can’t blame him for what he went through. It was awful. He said it took his father to say, “You’re alive. Look at the alternative.” He said that’s what made him move on. Do you think it’s your surroundings of your family saying, “I’ve had enough of this,” that made you accept it and go on?

I don’t think that I was that mature at that point. I went through a period where I wanted to get back because I had nothing else due to some personal setbacks. During that period of my life as well, I had been engaged to a woman before I was injured and then we broke off our engagement about a week after I was hurt. I had been spiraling downward with the help of a couple other women that I started seeing. I made a mess of their lives and my life. I got to the point where nobody wanted to put up with my selfish shenanigans. I was thinking, “What else do I have in my life? That’s right, I know how to operate in these types of places, so I’ll go back there and do that,” and that was it.

Weren’t you scared when you went back?

I was terrified not to go, but then when I got on the ground, I thought it was a terrible mistake, “I shouldn’t be here.” This was when the plane landed in Kabul. When I landed in the capital at the airport, I was drenched in sweat. It was in the middle of summer. I was scared. I didn’t know what I was doing there, whether I was going to be able to walk out of the airport. I was so frightened. Then I put one foot in front of the other and said, “This is what I have to do and this is what I’m here to do. I might as well do it.” After about two months, I started to finally settle down and settle in.

Do you still get scared?

[bctt tweet=”I put one foot in front of the other and said, This is what I have to do and this is what I’m here to do. I might as well do it.” username=””]I’d be pretty not to be. There’s no bravery in not being afraid. Being braver, being scared and propelling yourself forward but not being scared is interesting.

Fear keeps us alive as we have that natural instinct for that. It’s interesting to me that this happened eight years ago and your book’s come out this year. What took you so long to write the story?

I sat down to write the book in 2014. Then it took me three years to find someone that wanted to publish it.

I’m surprised because that was quite a story and with your background.

I was pretty surprised though, frankly. When you write a memoir when you’re not famous, it’s hard to get published. When the whole cast of the Jersey Shore had their own books, it’s a tough market.

It’s interesting as I’ve had Molly from Molly’s game, and I don’t know if you saw that movie, Eric O’Neill from the movie, Breach. Both of them have been on my show and they have stories like yours where you’re listening to the whole time. You can’t believe this happened. They both said the same thing. It’s not easy to get your story out there. Eric put and took down the biggest buy in US history as an FBI agent and eventually, they made it into a movie. Do you see if they could make this into a movie?

I’ve had people inquire about it. It has some cinematic appeal and qualities to it. Sure, why not? It’s not a deep dive look into Afghanistan, so it’s not a nuanced political book in that sense. It’s more of a story about overcoming and making a mess of your life and then trying to figure out how to put all the pieces back together. There are many more self-inflicted injuries in the book than the one I got from the Taliban. It’s a story that a lot of people can relate to because we’ve all been in a position where we stepped on the proverbial rake and had the handle smack us in the face.

We’ve all been there. I tried to write it in a way where the book is not bogged down in military jargon and a deep dive look at strategy. It’s not that type of story. It’s the kind of story anybody can get into. Most of the folks that I’ve heard the most from are people who have had no connection to the military, who have never read a book like this before and have been able to get something from it. It has that potential for sure.

Do you go into other aspects of your life in this book? Is it mostly what happened to you?

The tagline that I often use for the book is that getting shot in the face was the start of the story and it is. It’s at the beginning of the book. Most of the book takes place outside of Afghanistan. It’s me back on the stage trying to put myself back together, both physically and mentally and failing miserably to do the ladder, all the while thinking that I could capitalize on the fact that I had gotten hurt and played on other people’s sympathies. Also, the fact that I’d broken up with my then fiancé. There was a lot of heartaches involved there. I used all that to augment my masculine wiles and I did a lot of bad stuff that I shouldn’t have. I felt bad about it.

Did she break up with you because of what you went through, that she couldn’t deal with it?

We were having problems before that. We had a date set and a venue picked out. We were raring to go and then it all came tumbling down. If you read my book, you’ll see how all that went down. I don’t wallow in my own misery. It’s a very self-deprecating, dark humor story. It’s not one that you’re going to find that’s all morose. There are serious moments, but I’ve had people tell me that they laughed throughout the book and at many times feel bad about laughing. I’m telling things that happened and it was my sense of humor that ultimately saved me in this ordeal. Otherwise, I would have lost it.

I wonder thinking of your fiancé what she thinks of having to break up with you at that point. There’s nobody who’s going through this and who’s going to have an easy time of it. Forever she’ll be the one who left you when you were going through this, no matter if that was the reason or not. Forever your parents will wonder had they have stopped you and everybody thinks from their perspective. That’s my point. What’s fascinating when I was watching this video was how calmly you handled this horrible thing. When you’re in shock you don’t know how you’re going to handle something. There was no screaming or yelling. You’re like, “This is bad about it. I know it’s bad,” or however you put it.

A lot of my colleagues are constantly kidding me about that because in the video you hear me inquire about the whereabouts and the survival of my camera. I’m more concerned about my camera than I have on my own face. I’m a freelance journalist. I can’t readily replace that thing. I thought, “What am I going to do without my camera?”

It went black for a minute and what was that about?

The camera tumbled to the ground and it kept rolling. After that incident, I didn’t turn it on for about six months because I wasn’t sure whether I caught the attack on film and I didn’t want to find out. That camera sat in a box for about six months. Then one day, I charged the battery and I turned it on. I hit play and there it was. This is something I chronicled in the book as well. I had a friend of mine who went through the footage with me and it was reliving the incident all over again. I’ve only seen the entirety of that footage that one time. There’s a chapter in the book dedicated to that period. That camera, I kept using it for another two years, three years after that incident. I kept using that same camera. I took it to a shop. They gave it once over and I took it back to Afghanistan with me when I went back. It’s been on subsequent trips to Iraq. It’s been all over the world and I retired it back in 2013.

[bctt tweet=”We’ve all been in a position where we stepped on the proverbial rake and had the handle smack us in the face. ” username=””]My daughter left her iPhone and it fell out in the water. It stayed in the lake overnight and the next day it turned on. Sometimes we get this thing. I’ve had three dishwashers in about a year and none of them can work. You never know what your reaction is going to be watching the video. I find that fascinating that you waited six months because you don’t know what you’d do in that setting. To me that would be so interesting, I want to know what happened. I want to know what happened to the guy who shot. Did they find him? Did you get him on tape? You didn’t and they didn’t find him, I assume.

I didn’t get them. Something that I mentioned in my book is that at one point I even started to feel bad for the guy that had shot me because if you think about it, here he was he had me dead center. There was a whole platoon of soldiers. He’s in close range, no obstructions. The guy is one-on-one down the road. He hits me in the side of the face and the rocket doesn’t go off. Can you imagine his fellow Taliban? They probably harassed him to death and busted his balls about the fact that he couldn’t kill one unarmed reporter with an RPG. He’s probably still getting hell about all that.

I love that you look at it that way. If you hadn’t turned around, do you think it would’ve been better off?

I have no idea. If it hit me in the back of the head, then it would have killed me for sure from the impact. The back is so much more delicate than the front of your skull and I have a thick head, fortunately.

How many people were with him? Was it just him and another guy or what was it?

I just saw one guy, so I don’t know if there were others. There may have been a follow-up attack, but they were probably laughing themselves silly crouching behind some rocks somewhere and figured, “If that man can’t kill one guy with a rocket-propelled grenade, what are we going to do? We’ve got to call this one off. We’ll try again another day.”

What I find interesting about all that is your empathy, which is a big sign of emotional intelligence by looking at it from the other person’s perspective. I’m wondering with all of this reporting that you’ve done and you see this fighting from both sides, do you change your idea of who’s the good guy and who’s the bad guy?

I even mentioned in my book that I feel my reporting is limited in my ability and scope of what I can do because all of my time is spent on one side of the fight with the US Forces. I’ve only had so many opportunities to come in contact with the Taliban. I’ve interviewed members of the Taliban in more controlled settings, never in the mountains and a frontline situation. You could embed with the Taliban and it’s called kidnapping, but I’ve never been embedded with them. I’m very forthcoming about this, I might have reported it inherently flawed because it only comes from that one side. I speak to Afghans, but you don’t get both sides in ways that you could in the previous conflicts.

I have older colleagues who covered the civil war in El Salvador in the ’80s and they would tell me stories about how in the middle of a firefight, they would flank a firefight. They’d be on the side of the rebels and they would walk around to the other. They could go around the firefight and go behind the front lines of the soldiers. They’d be on their side in the middle of this team fight and nobody would try to kill them. They got killed, they got hurt and injured, but nobody was targeting them. They were press. Those sides acknowledged the fact that they were there to cover the conflict. They could do that kind of thing because there were a lot of close borders fighting that way and it was crazy. The stories I heard from those guys were unbelievable. You have that opportunity and not in a fight like Afghanistan and other conflicts that I’ve covered.

You must have seen a lot of children and issues that you don’t see here in the United States of how they’re involved and their perspective of the war. How does that change you?

What I’ve come to realize is that the generations of children now in Afghanistan, they’ve been fighting since ’79, the Soviet invasion. It’s been nonstop conflict in that country since then. You’ve got generations of children now, adults who’ve grown up and understood nothing but war, who have not been able to go to school. That access to education into a normal civility breeds more hatred, misunderstanding, and fear, which is a perfect recipe for an insurgent fighter, a militant, a Taliban, an Islamic state or other militant groups you have in Afghanistan. It’s a self-perpetuating process.

It’s something that I’ve come to realize. For example, in Iraq and in Syria, when you have a relatively stable society before the war and then everything breaks down, kids can’t go to school. If kids can’t go to school for the duration of a war let’s say five, seven years, that’s five, seven years of their education that they’re missing out on. If the war breaks out when they’re six and it ends when they’re thirteen, those are the formative years in which they were not only learning their A, B, Cs and one, two threes, but they’re learning how to become a normal and adaptable human being. All of that is taken away from them and now they will never get it back. When you have that situation, it takes two generations of stability to make up for a fraction, let’s say six or seven years of instability. These are wounds that are not easily repaired and a generation can be lost. That generation loss can infect the next generation if the dramatic efforts aren’t taken to repair and make amends for what had happened.

That’s what we’re going to see in Syria. We’re on seven years now of fighting. 500,000 people were killed at seven years of disruption where people are living in refugee camps in Turkey and then staying in Lebanon and Jordan and elsewhere where children are being educated. They don’t have the opportunities that their parents did. They’re jaded, upset, and scared. They don’t know what their future is going to hold. Who comes along and offers them a steady paycheck and three-square meals? An Islamic State. That happens. That’s something that is going to be affecting the future generations for many years, I’m afraid.

Hearing everything we hear about in the world, it makes you afraid to fly and not just to fly but to travel anywhere. I have a friend who was in a refugee camp after being in Bosnia. When you talk about, “I feel comfortable going to Europe.” With her, she thinks it’s almost worse to go there than maybe other places she’s more comfortable. Her perception of where we can go, where we’ll feel safe has been so much of impact for me, at least in my generation. A lot of people say Lebanon is not as bad as other places to go, but do you feel safe going there? Do you feel like every place that we think are safe are not safe? I’d be curious on your perspective on how safe you feel in different areas that other people don’t see as bad?

I’m going back to the States. That’s what scares me.

The United States? Why?

Yes, I was in New York in May and it made me nervous. I was in DC after that. That makes me nervous and I have lived in both. For me, it’s not terror-related. I’m not worried about that. I worry about many other things. I worry about the fact that there are other domestic terror-related incidents going on. I’m jumping off as it is now. If a car backfires and I’m in the States, I’m on the ground. I’ve watched enough TV and I know the news. I’m looking for shooters and that’s what scares me.

You’re talking about driving by kind people.

No, I’m talking about mass shootings in Parkland and Vegas, that kind of stuff. I think about that and that scares me. I think about the possibility of that happening because it can happen anywhere as we will have seen. It tends to happen in more suburban places. I’m scared of the suburbs. That’s what scares me.

It is scary. It was hard to go to Vegas after that or different places. I haven’t even gone to New York in a week or so. It’s in the back of your mind. It’s hard not to think of that as you travel. There’s no place that’s safe, which is sad. That’s the time like that. Your book is very unique and different. I’ve never seen a video or anything like you survived. A lot of people should definitely go to your site to watch that video and get the book because it’s fascinating. Your website is your name, CarmenGentile.com.

My book is easy to find on Amazon, Blindsided by the Taliban. I also have a Facebook page for the book and I’m easy to find on social media. I’m the guy with the girl’s name who has an eye patch. It’s hard to miss me.

It is hard to miss that. Make sure they could find your website because you have some fascinating pictures and follow-up there. I wish you success with your book. I’m impressed with what you were able to come through and your outlook is positive. I look forward to the success of your book. Thanks for being on the show.

Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

You’re welcome. I want to thank Carmen for being my guest. He had an amazing story. I have had several guests who have had real life, amazing stories and we mentioned them on this episode. There are so many amazing stories that are true life and that have impacted me. If you’ve missed them, I hope you check them out. Also if you’re looking for more information about the Curiosity Code Index or Cracking the Curiosity Code book, they’re both at CuriosityCode.com. I know we talked about that a lot in different episodes. That’s it for this episode. I hope you join us for the next time.

Important Links:

- Carmen Gentile

- Blindsided by the Taliban

- Carmen Gentile’s video

- Tanner Gers – previous episode

- Erik Weihenmayer – previous episode

- Molly – previous episode

- Eric O’Neill – previous episode

- CarmenGentile.com

- Blindsided by the Taliban on Facebook

- CuriosityCode.com

About Carmen Gentile